July 2018: Vincent Mai travels from Canada to teach a 2-week Duckietown class to some of the brightest high school students in Ghana.

The email – Montreal, January 2018

On the morning of January 29th, 2018, I received an email. It was a call for international researchers to mentor for two weeks a small group of teenagers that will have been selected among the brightest of Ghana. Robotics was one of the possible topics.

At 4 pm, I had applied.

I was lucky enough to grow up in a part of the world where sciences are available to children. I spent summers in Polytechnique Montreal, playing with electro-magnets and making rockets fly with vinegar and baking soda. I also remember visiting the MIT Museum in Boston, where I was impressed by the bio-inspired swimming robots. There is no doubt that these activities encouraged 17-years-old me to choose physics engineering as my bachelor studies, which then turned into robotics at the graduate level.

The MISE Foundation

The call from the MISE Foundation was a triple opportunity.

First, I could transmit the passion I was given when I was their age. Second, I would participate, in my small, modest way, in the reduction of education inequalities between developing an developed countries. Countries like Ghana can only benefit from brilliant Ghanaians considering maths, computer science or robotics as a career.

Finally, it was an unique opportunity for me to discover and learn, from people living in an environment that is totally different from mine, with other values, objectives and challenges. It is not everyday you can spend two weeks in Ghana.

After some exchanges with Joel, the organizer, with motivation letters, project plan and visa paperwork, it was decided: I was going to Accra from July 20th to August 6th.

The preparation – Montreal, June 2018

My specialty is working with autonomous mobile robots: this is what I wanted to teach. I was going to see the brightest young minds of a whole country. I needed to challenge them: I could not go there with a drag-and-drop programmed Lego.

I chose an option that was close to me. Duckietown is a project-based graduate course given at Université de Montréal by my PhD supervisor, Prof. Liam Paull. It allows students to learn the challenges of autonomous vehicles by having miniature cars run in a controlled environment. A Duckiebot is a simple 2-wheel car commanded by a Raspberry Pi. Its only sensor is a camera.

Along with my proximity with Duckietown, I chose it because making a Duckiebot drive autonomously is a very concrete problem, which involves a lot of interesting concepts: computer vision, localization, control, and integration of all these on a controller. Also, for teenagers, the Duckie is a great mascot.

I had not yet taken the Duckietown course. Preparing took me one month and a half of installing, reverse engineering, and documenting. The objective I designed for the kids? Having a Duckiebot named Moose follow the lanes with a constant speed, without getting out of the road or crossing the middle line.

It was inspired from a demo that was already implemented in the Duckiebot. I could not ask the kids to implement the whole code, so I cut out only the most critical parts of it. I also wrote presentations, exercises, planning each of the 10 days we would spend together, 6 hours a day. I packed the sport mats to do the road, a couple of extra pieces in case something broke, and the print-outs of the presentations. I was ready.

Packed Duckietown

Or, I hoped I was. It was not simple to adapt the contents of a graduate course for kids of whom I had no idea of the math and programming level. Did they know how to multiply matrices? What about Bayes law? Can I ask them to use Numpy? When I asked advice to Liam, he told me with a smile: “I guess you’ll have to take the go with the flow…”

The building – Accra, August 2018

Accra is a large city, spread along the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. Its people are particularly smiling and welcoming. The Lincoln Community School, a private institution hosting the MISE Foundation summer school, has beautiful and calm facilities which allowed us to give the classes in a proper environment. There were 24 children in total: 12 were training for the International Maths Olympics with two mentors, while three teams of 4 students would work with a mentor on projects like mine. The two other projects were adversarial attacks on image classifiers and stereo vision.

The first two days, we did maths. I tested their level: they did not know most of what was necessary to go on. Vector operations, integrals, probabilities… We went through these in a very short time: they amazed me by the speed at which they understood.

We followed with the real project: autonomous mobile robotics.

-

See-Think-Act cycle;

-

computer vision for line extraction, from RGB images to Canny edge detection and Hough transform;

-

camera calibration for ground projection, from image sensors to homography matrix;

-

Bayesian estimator for localization, with dynamic prediction and measurement update;

-

and finally, proportional control for outputting the right commands to the wheels.

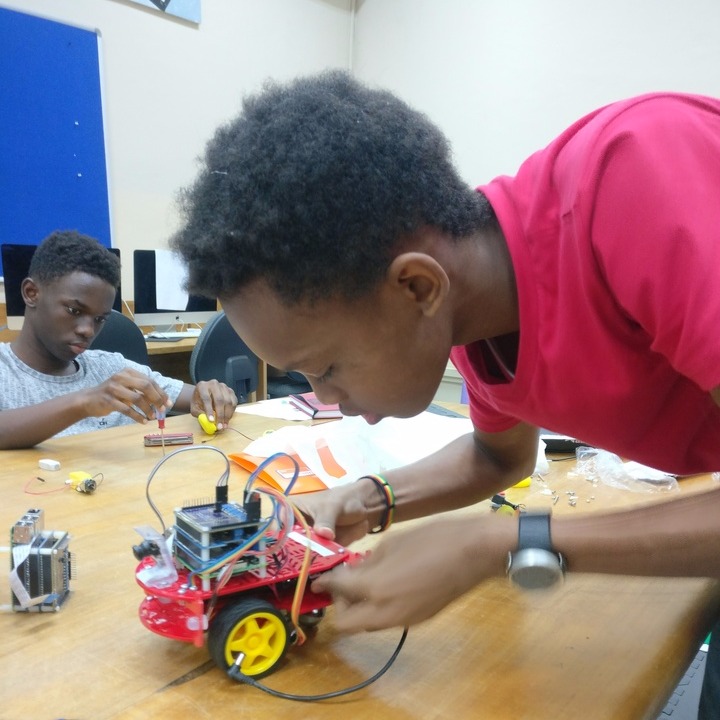

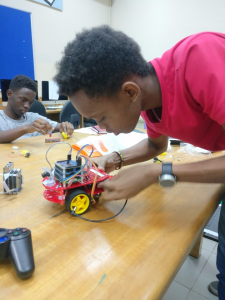

Building Moose

Moose the Duckiebot, up and running!

Moose the Duckiebot, up and running!

The experiments – Accra, August 2018

In the two next days, the students had to think what they would do for their research projects. The experiments would be done together but the projects should be individual. Each of them decided to focus on one aspect of autonomous cars. Kwadwo decided to go for speed: he tested the limits of the car as if it was an autonomous ambulance. Abrahim was more concerned about safety: was Moose better than humans at driving? Oheneba thought about the reduction glasshouse gas emissions and William about lowering the traffic. In both cases, they argued that if autonomous cars could improve the situation, they first had to be accepted by humans and therefore be safe and reliable. They tested Moose in differently lit scenes, with white sheets on the road (snow) or with a slightly wrong wheel calibration, to see how it would cope with these conditions.

On the last day, they individually presented their research to a committee formed by the three project mentors. We asked them difficult questions for 15 minutes, testing them and pushing them to think above what they had learned in these 2 weeks. We judged them based on the Intel ISEF criteria (Research project, Methodology, Execution, Creativity and Presentation).

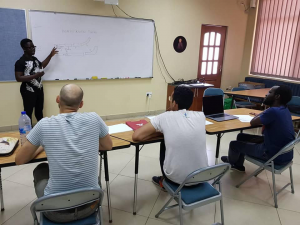

Presenting in front of the judging committee

Presenting in front of the judging committee

The closing ceremony – Accra, August 2018

Saturday was parents day. The students made a general presentation of their projects, making the parents laugh uneasily every time they asked “Is everything clear?” At least, I think most of the parents enjoyed the demonstration: it is always nice to see a Duckiebot run!

Finally, at the closing ceremony, the students who had the best presentation grades were rewarded. I was proud that Kwadwo was named Scholar of the Year, winning a Mobile Robotics book and the right to represent Ghana at the Intel ISEF conference in Phoenix, Arizona, in May 2019. He will present his project with the Duckiebot!

The students and organizers also gave each of us a beautiful gift: a honorary scarf on which it is written “Ayeekoo”. In the local languages, it means: “Job well done.”

I hope I did my job well, and that William, Oheneba, Kwadwo and Abrahim will remember Moose the Duckiebot when they choose their careers. I know that, in any case, these four brilliant young men will continue to shine. On my side, I really enjoyed the experience. I will make sure I don’t miss an opportunity to teach again to teenagers using Duckietown, whether it is in another country or here, in Montreal.

The best team!

The best team!

Important note

I had four boys in my group. You can notice on the picture below that, out of the 24 students, only 3 girls participated in the MISE Foundation program. When I asked Joel about it, he told me he has a very difficult time getting women to participate. At least 6 more girls were invited, but their parents would pressure them not to do maths and science, and discourage them from going to the Summer School. They feel this is not what a woman should be doing. I find this situation very frustrating. Ghana is a country with strong family values that are different from the ones I am used to. It is not our role as international researchers to tell them what is good and what is not. And, to be fair, software engineering presents similar ratios in Canada, even if the reasons are less tangible (maybe?).

On the other hand, engineers and scientists build the world around us, and they do so according to the needs they feel. Men cannot build everything women need. I strongly encourage any girl, in any country, who reads this blog post and who is interested about maths and computer science, to stand for what they want to do. We need you here, to build tomorrow’s world together.

MISE 2018 – Ayeekoo!

MISE 2018 – Ayeekoo!

Tell us your story

Are you an instructor, learner, researcher or professional with a Duckietown story to tell? Reach out to us!