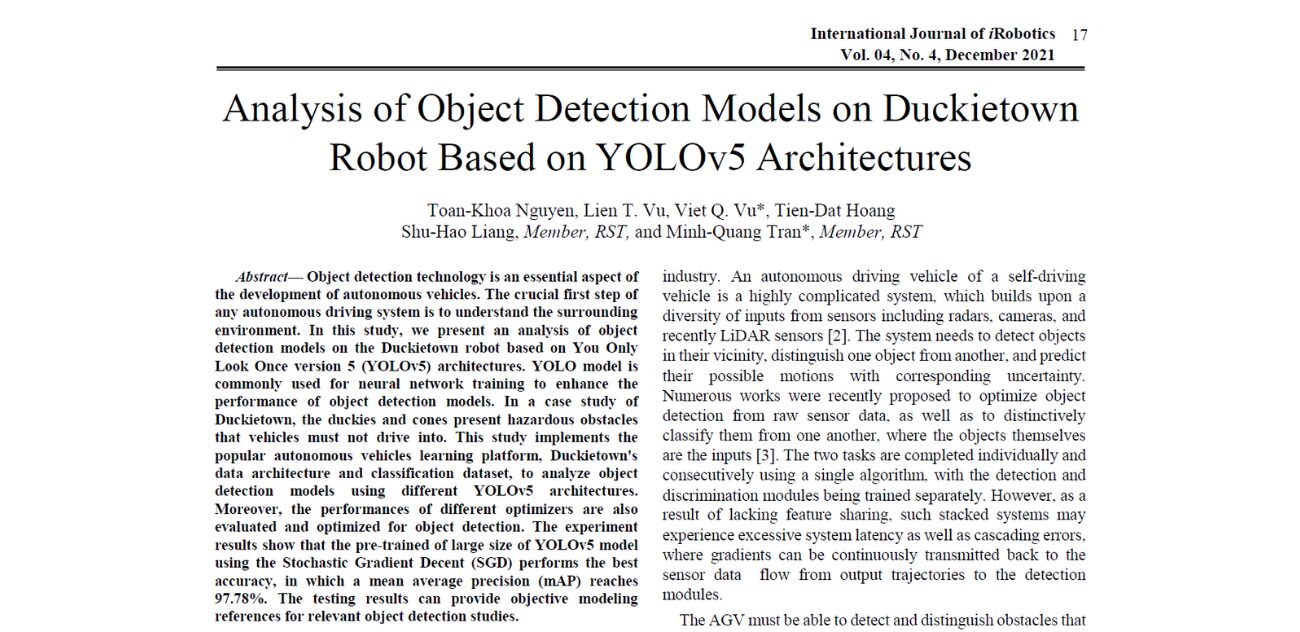

General Information

- Title: On Assessing the Usefulness of Proxy Domains for Developing and Evaluating Embodied Agents

- Authors: Anthony Courchesne, Andrea Censi, Liam Paull

- Institution: Montreal Robotics and Embodied AI Lab (REAL) at Université de Montréal, Mila.

- Citation: A. Courchesne, A. Censi and L. Paull, "On Assessing the Usefulness of Proxy Domains for Developing and Evaluating Embodied Agents," 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 2021, pp. 4298-4305, doi: 10.1109/IROS51168.2021.9635977.

Proxy Domains for Evaluation and Learning

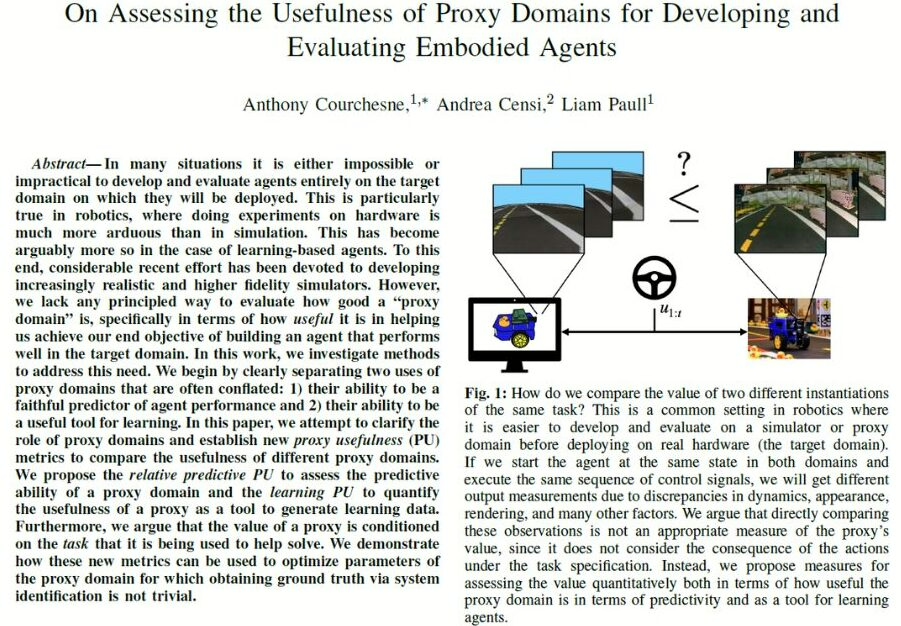

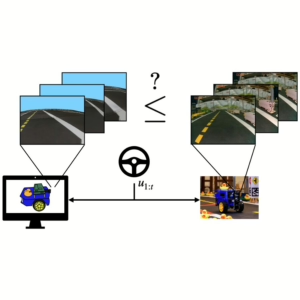

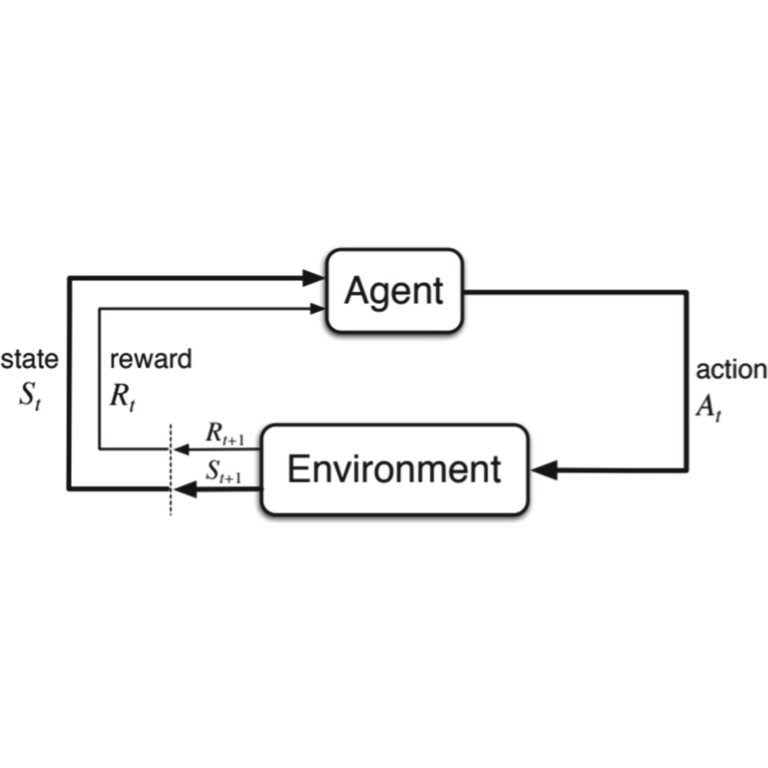

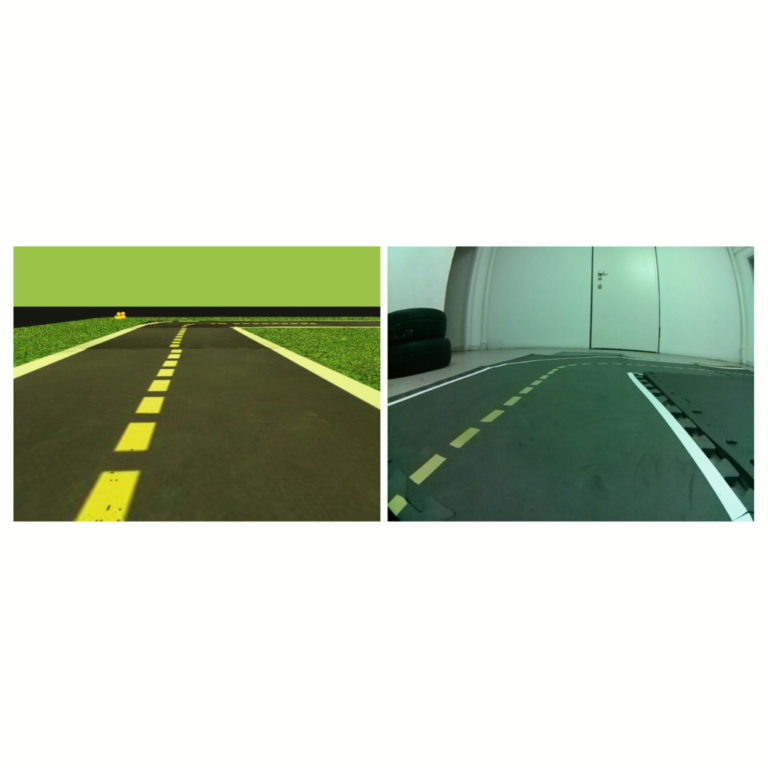

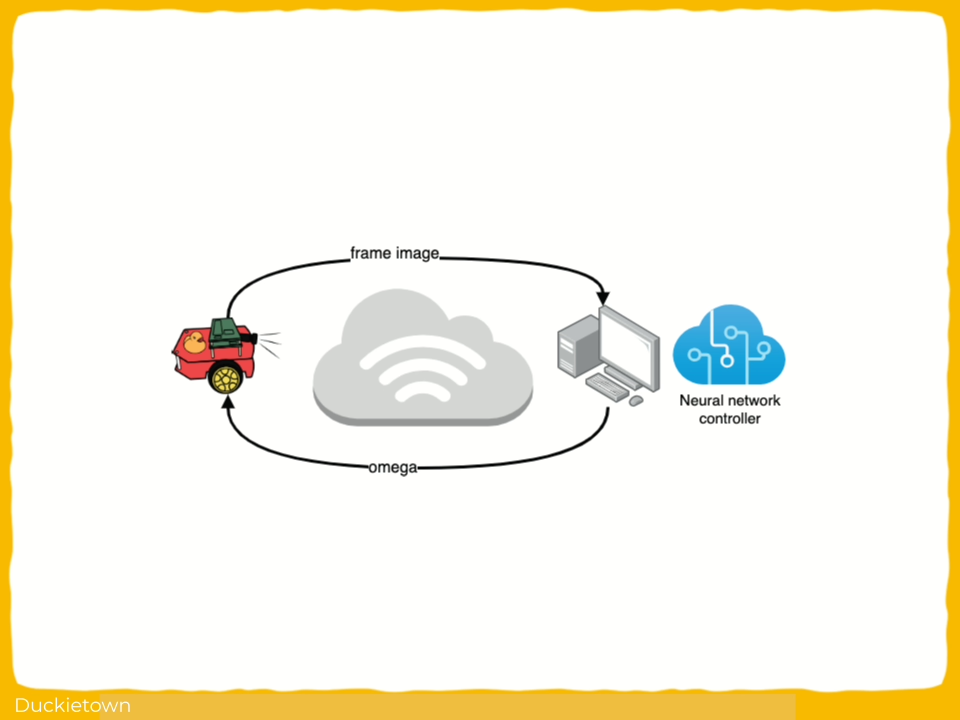

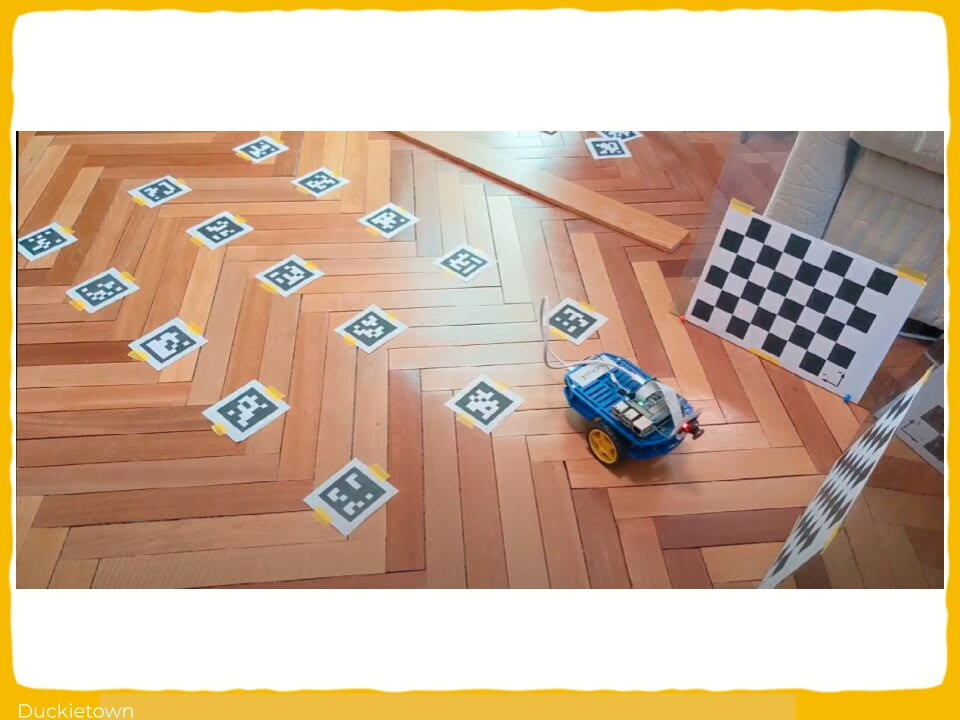

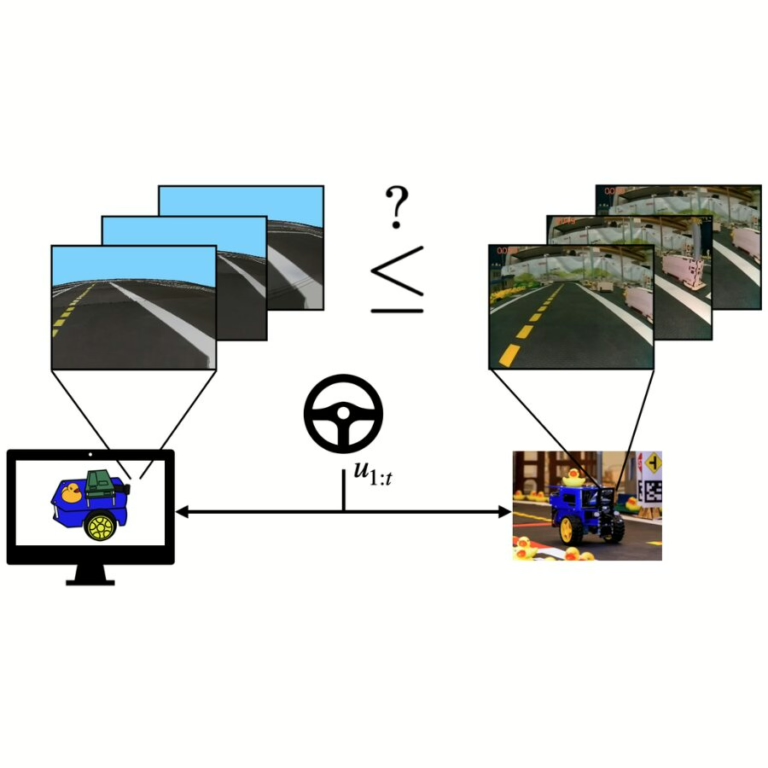

Running robotics experiments in the real world is often costly in terms of time, money, and effort. For this reason, robotics development and testing rely on proxy domains (e.g., simulations) before real-world deployment. But how to gauge the degree of usefulness of using proxy domains in the development process, and are all domains equally useful?

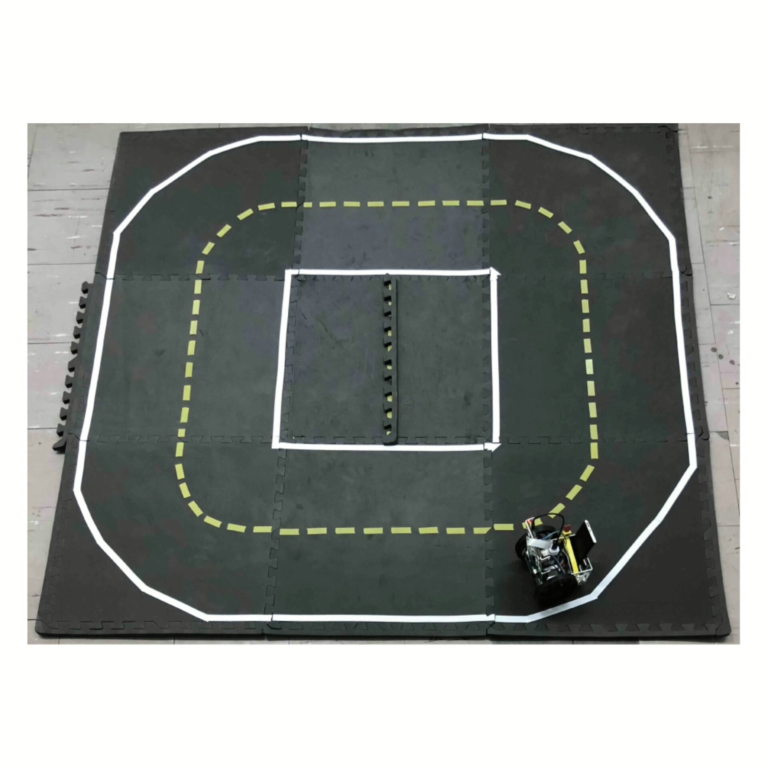

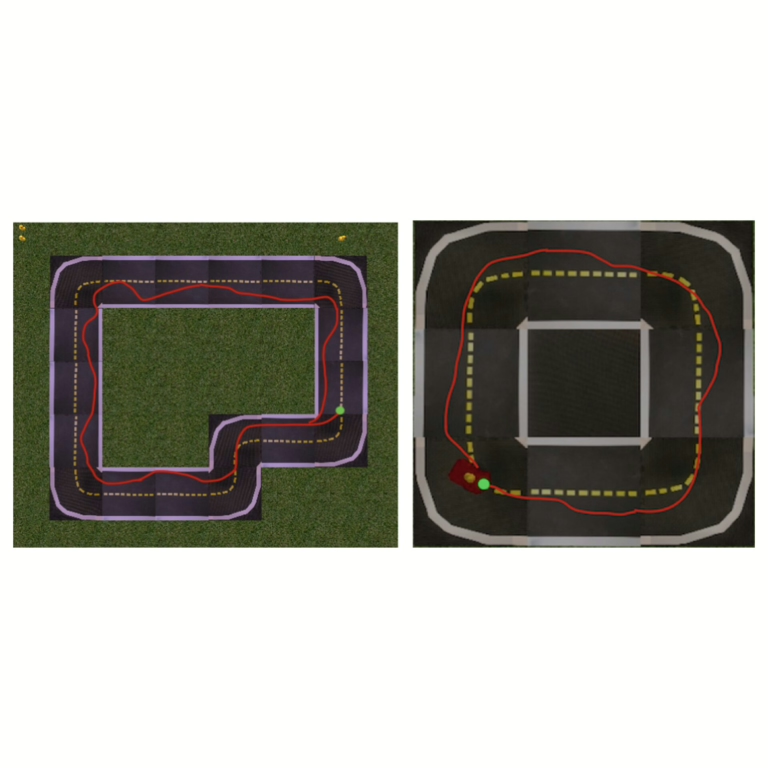

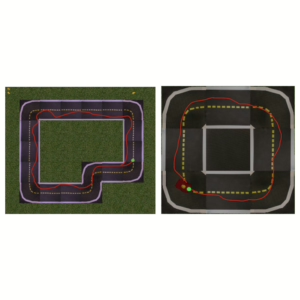

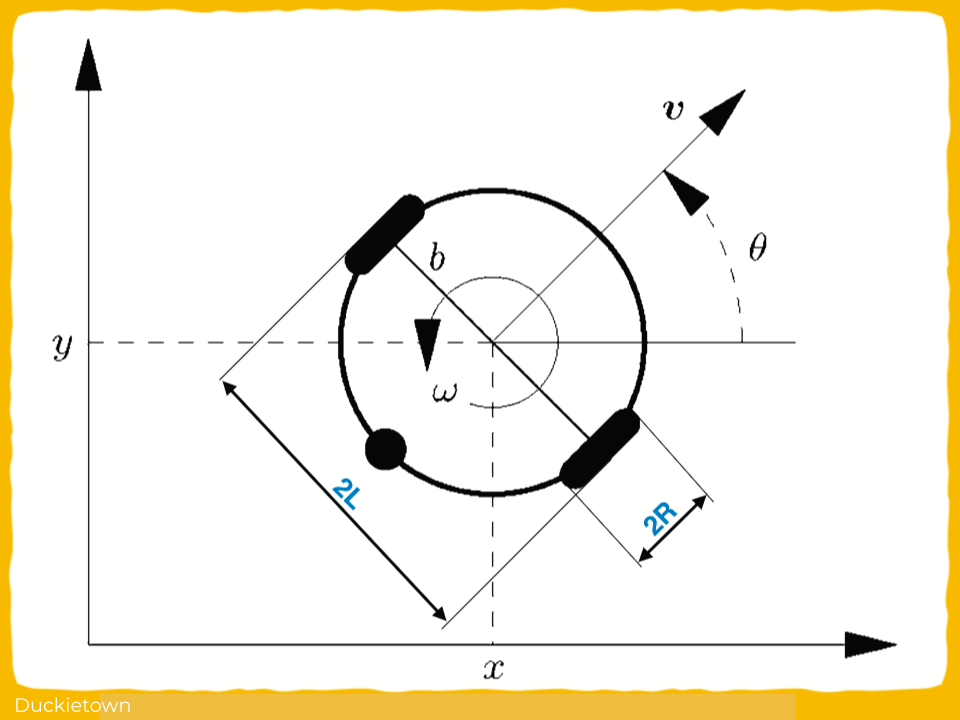

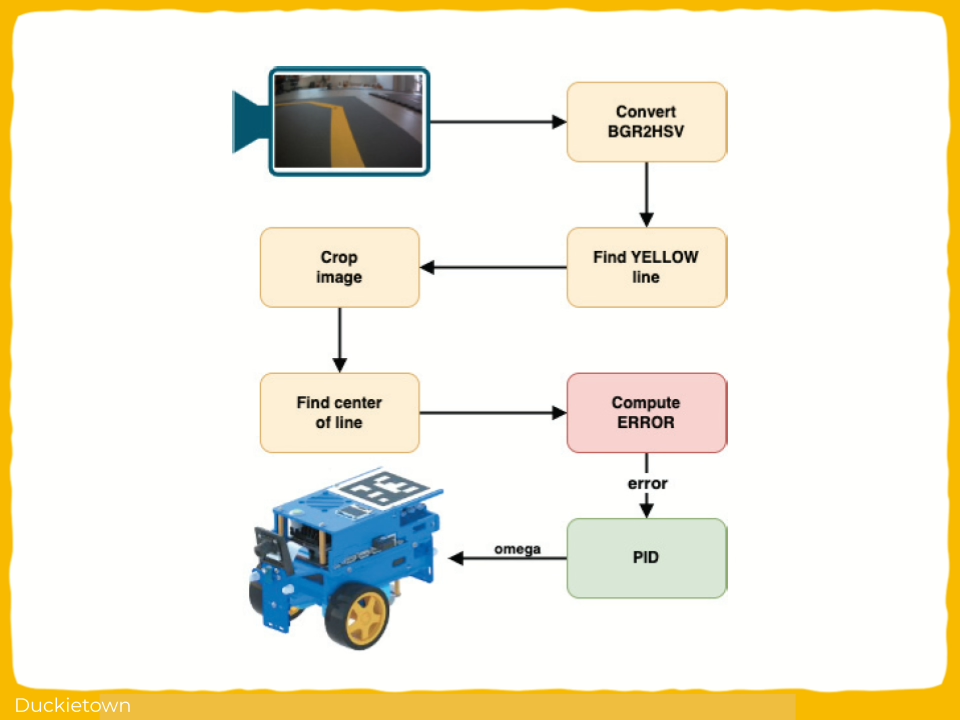

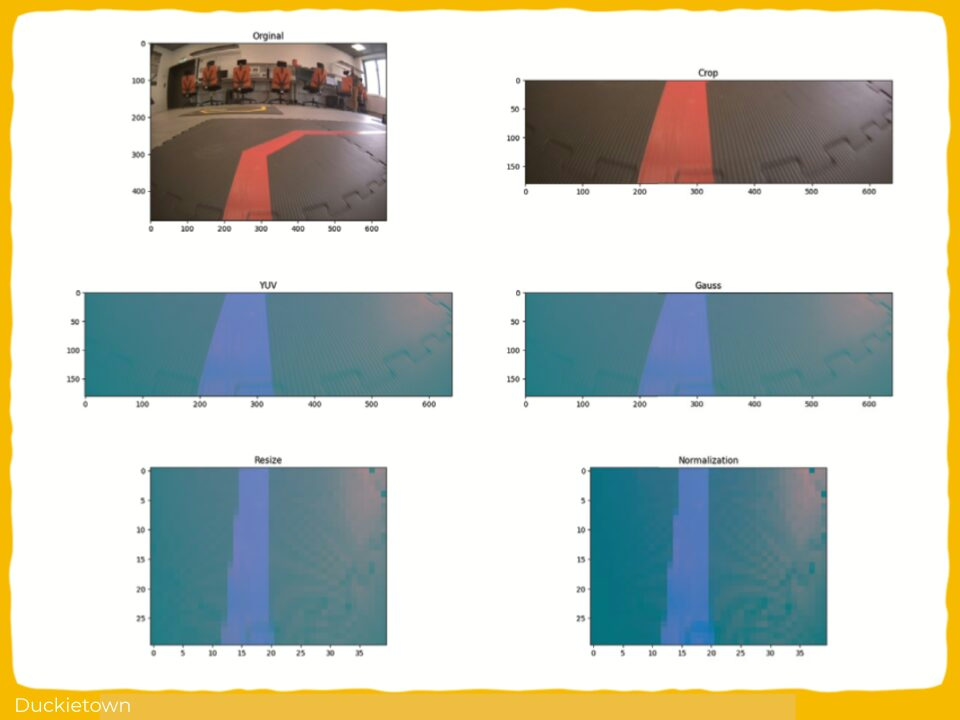

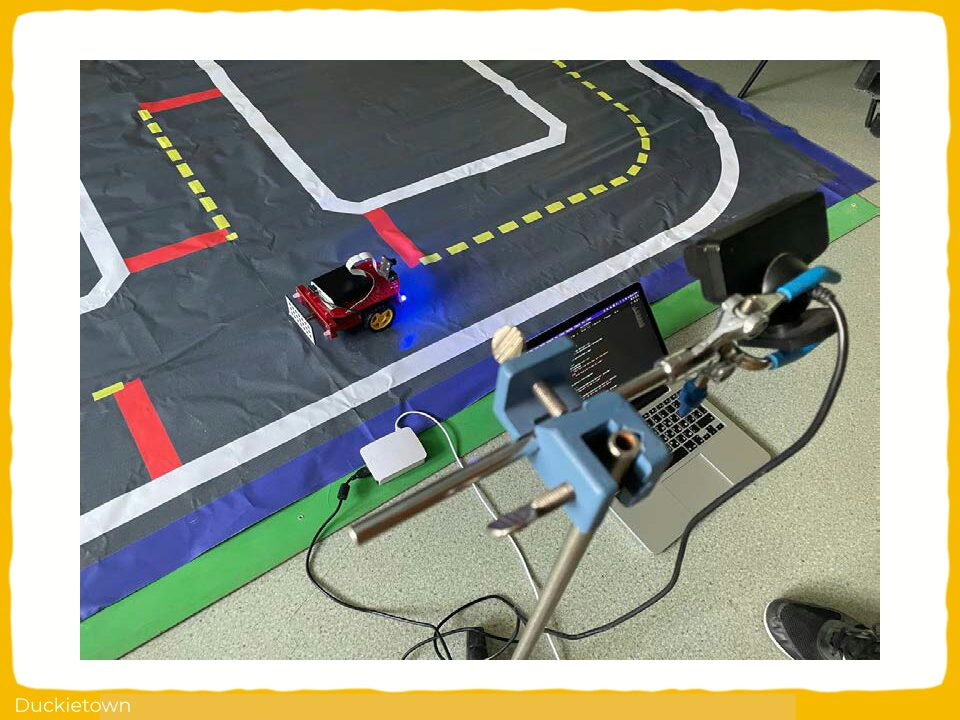

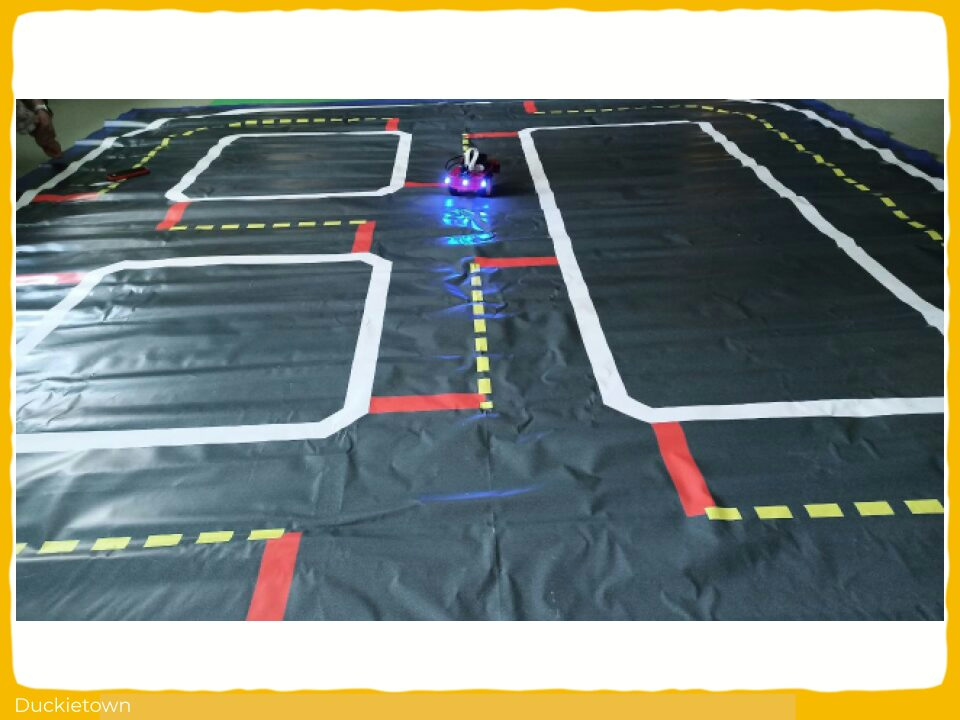

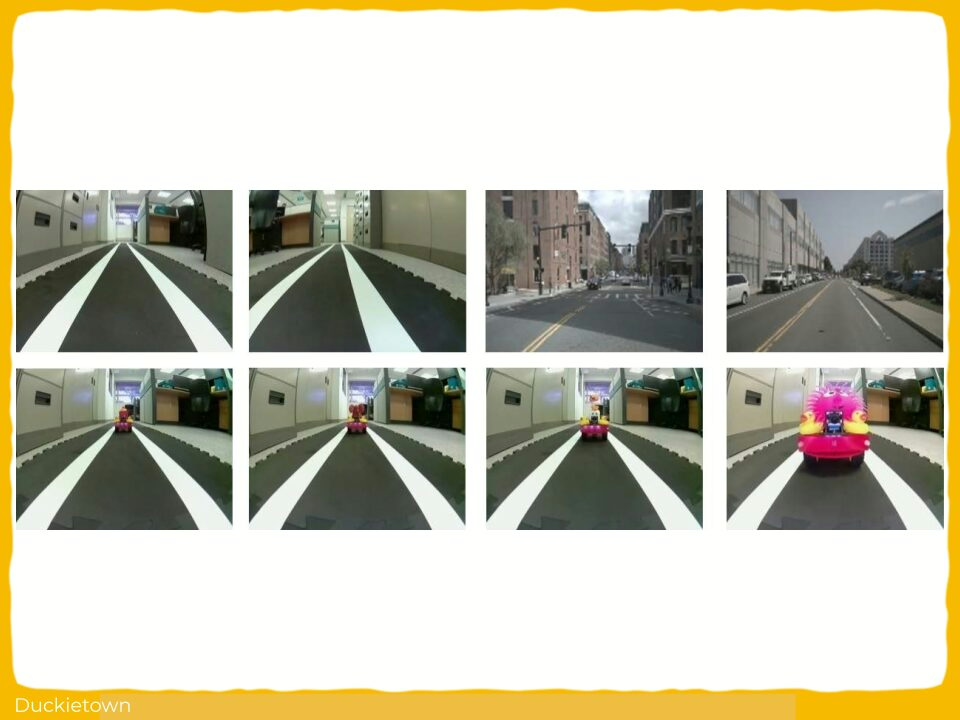

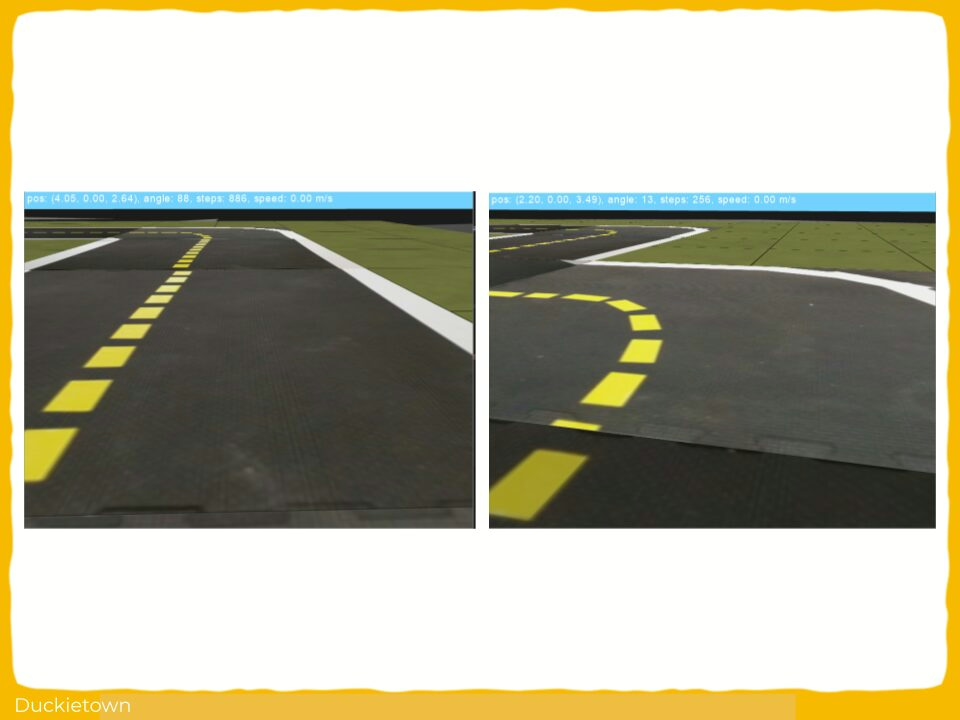

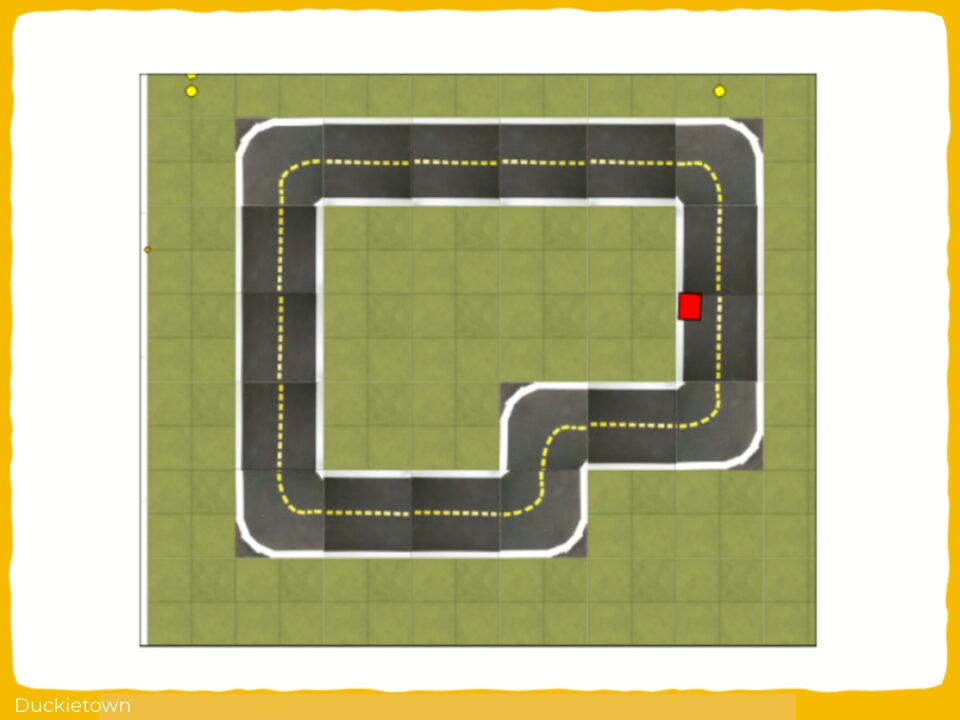

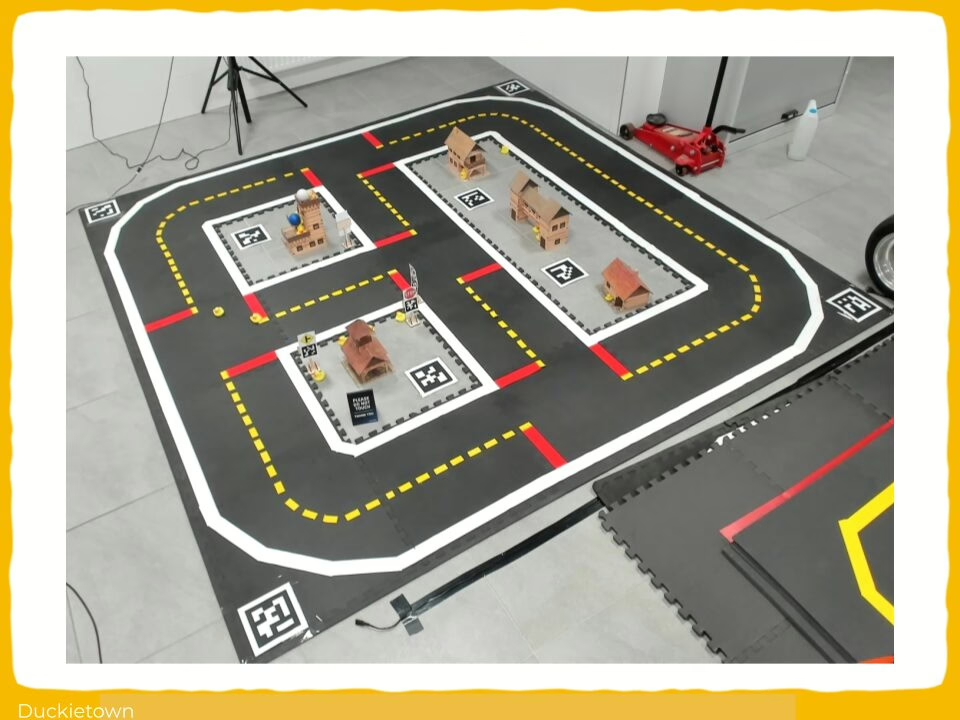

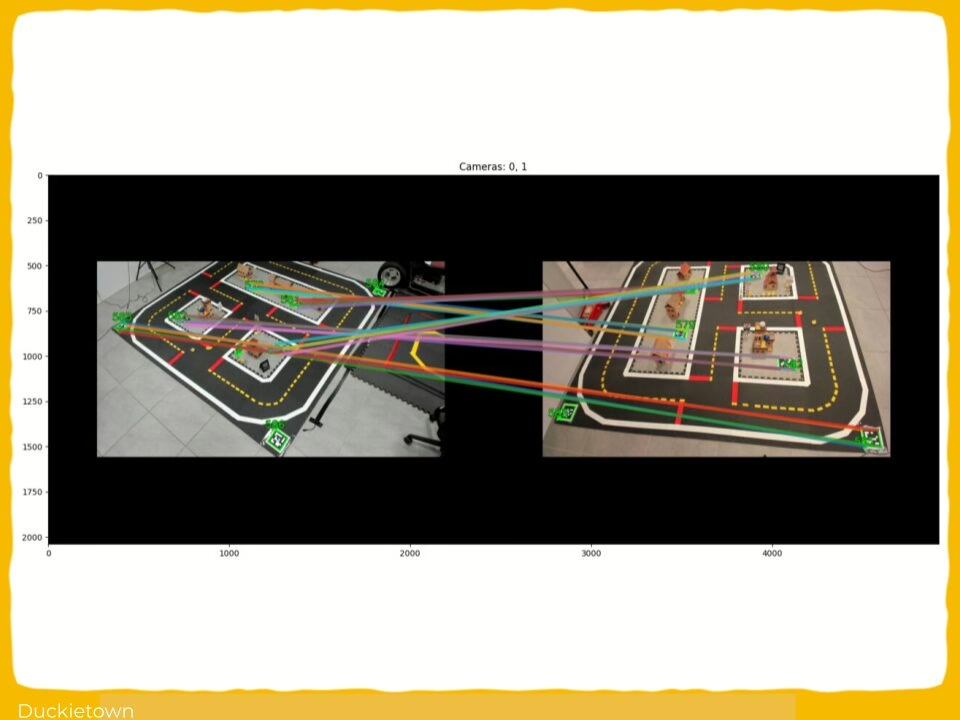

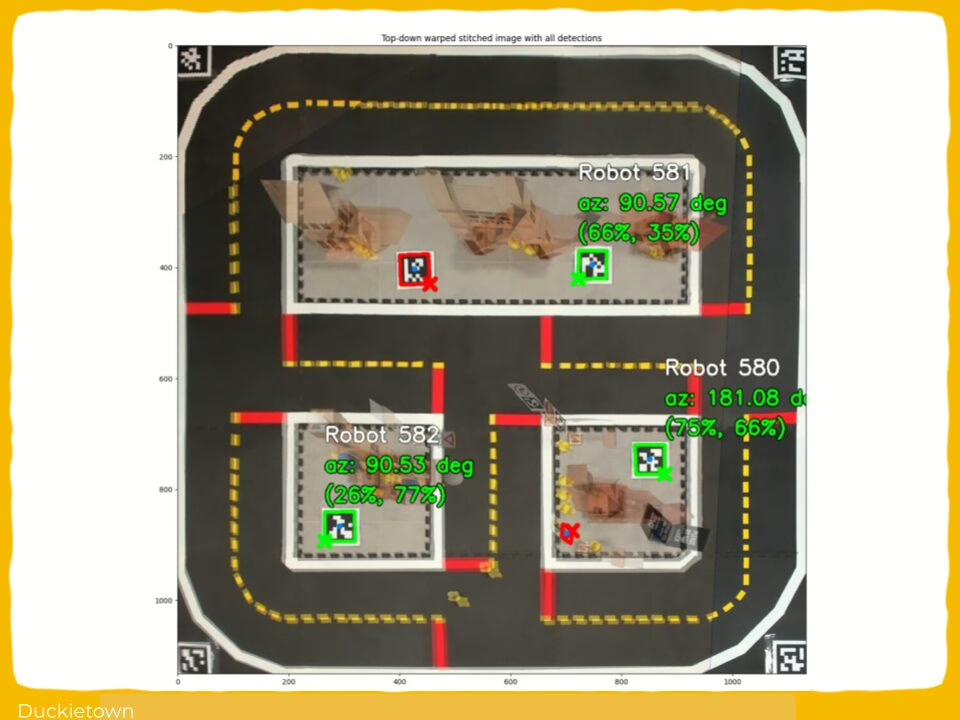

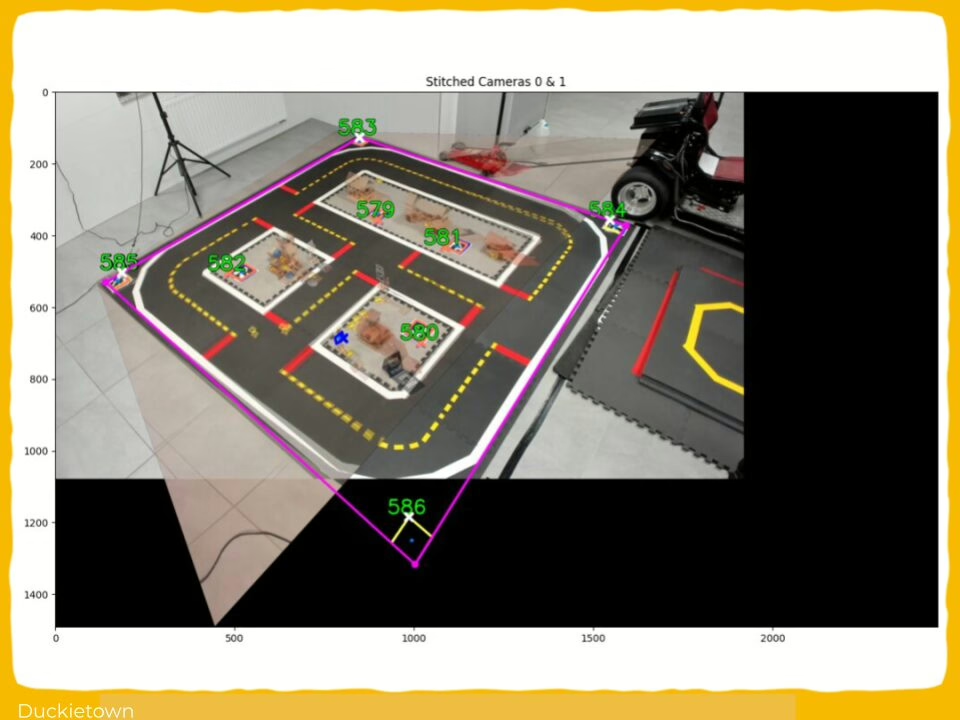

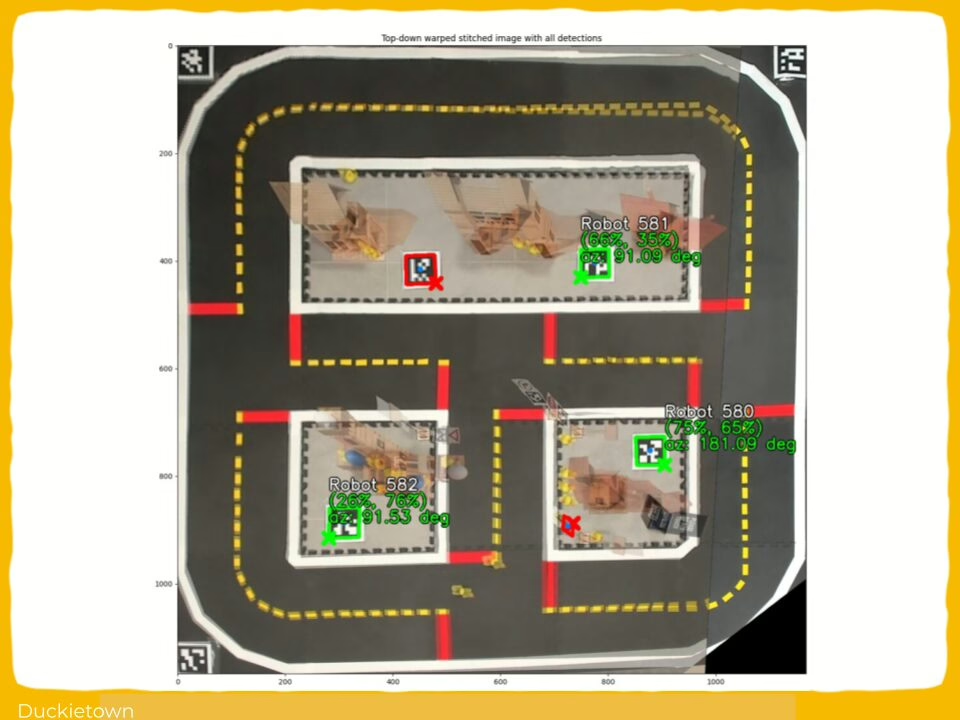

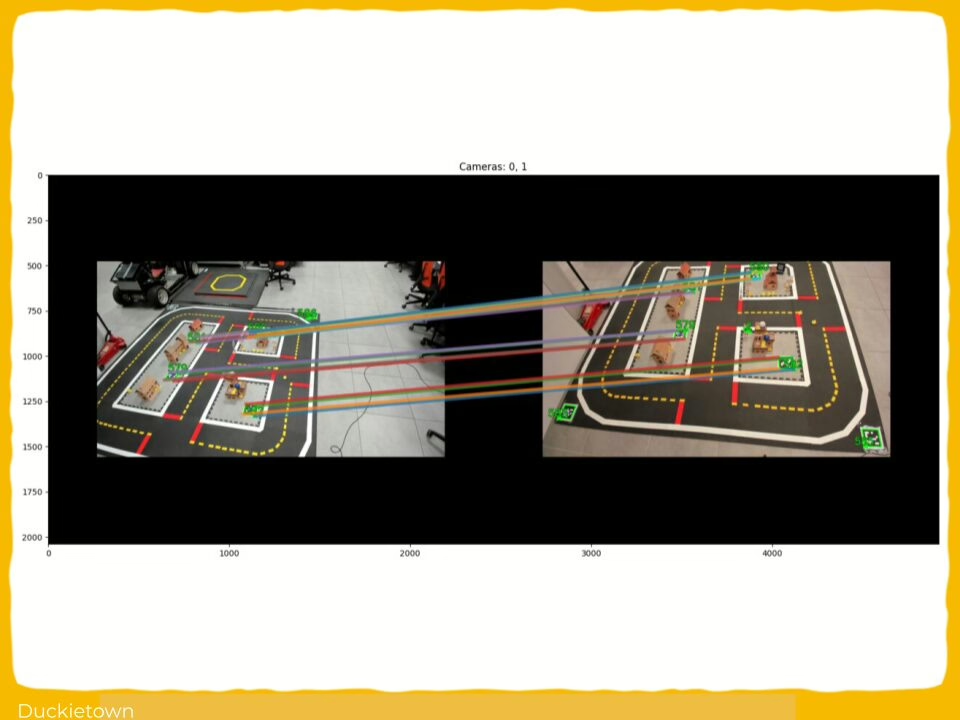

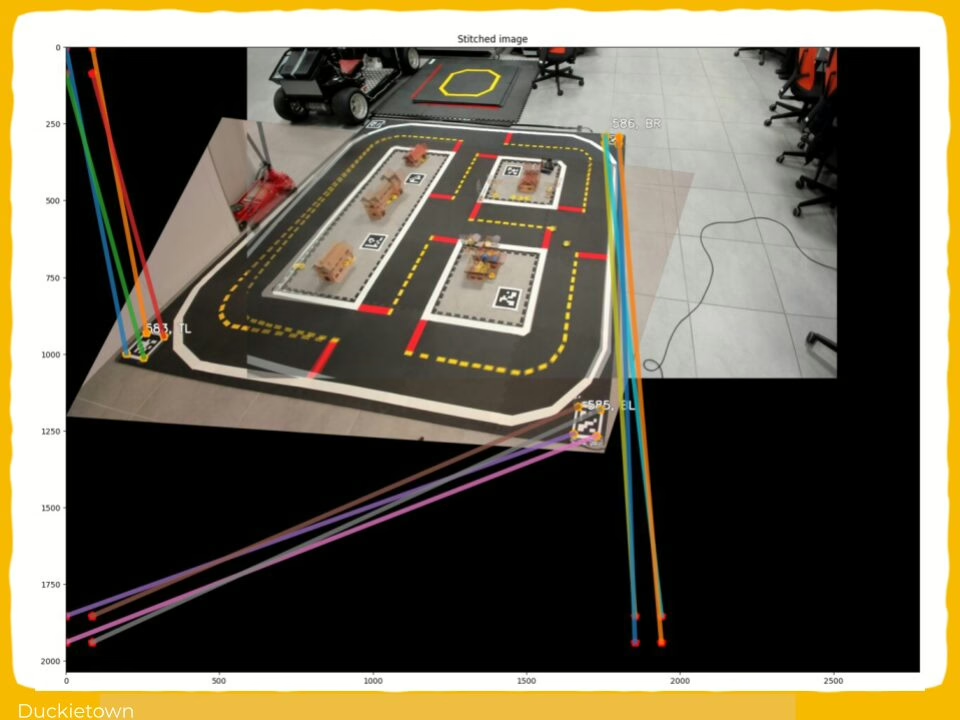

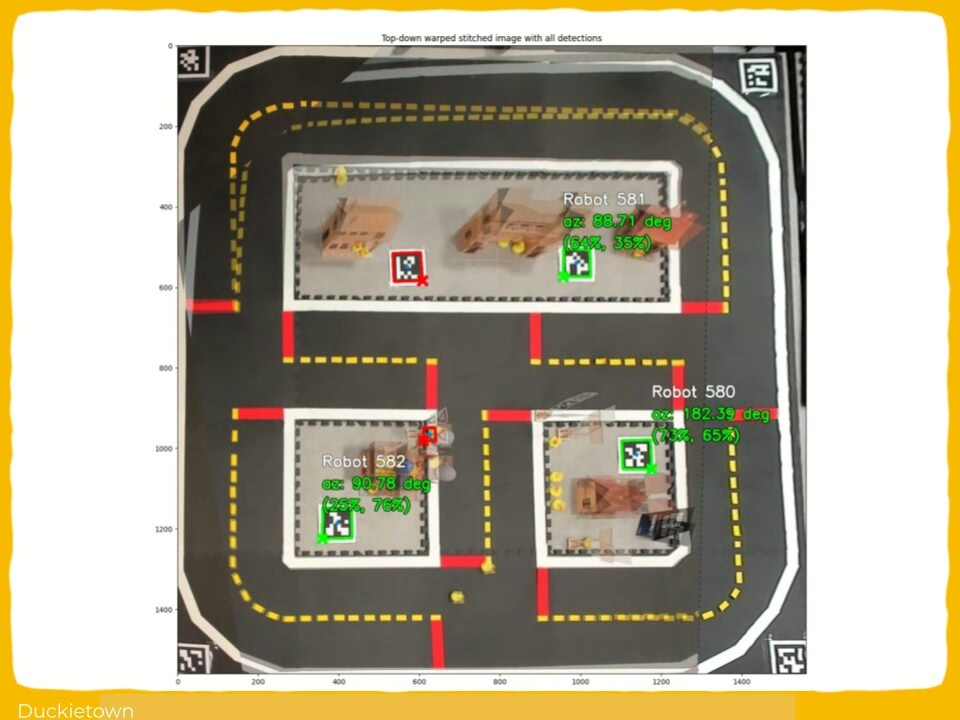

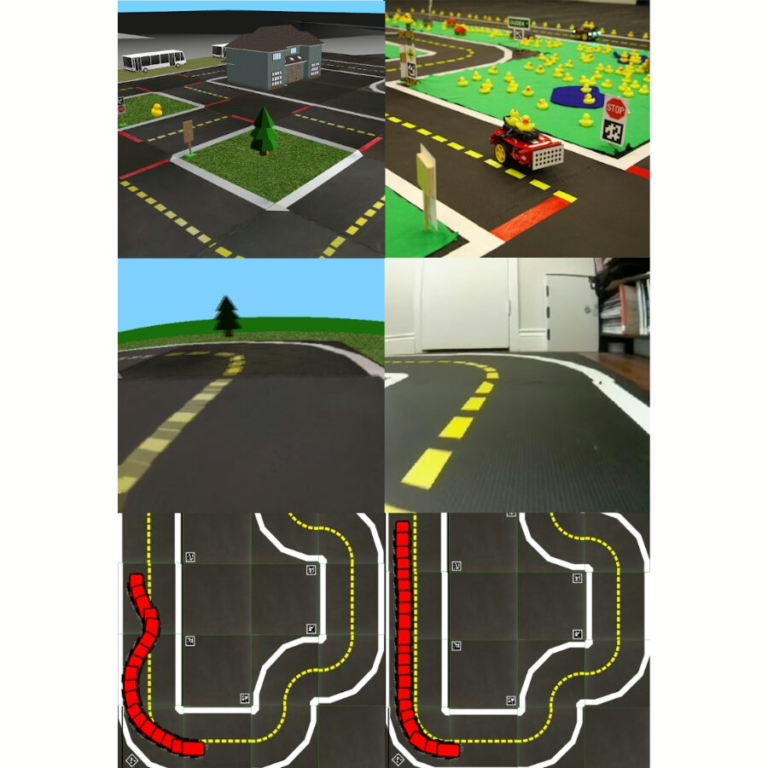

Intuitively, the answer to the above questions will depend on the type of robot, the task it has to achieve, and the environment in which it operates. Evaluating a proxy domain’s usefulness for a specific combination of these circumstances, specifically for the training of autonomous agents, is tackled in this work by establishing quantification metrics and assessing them in Duckietown.

The key aspects of this work are:

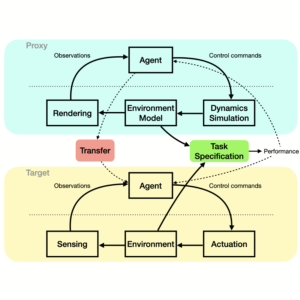

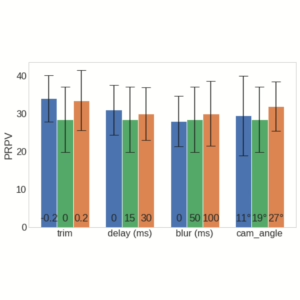

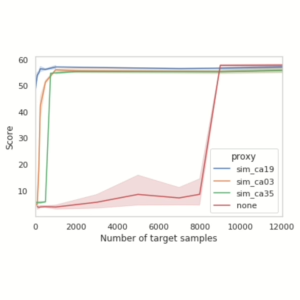

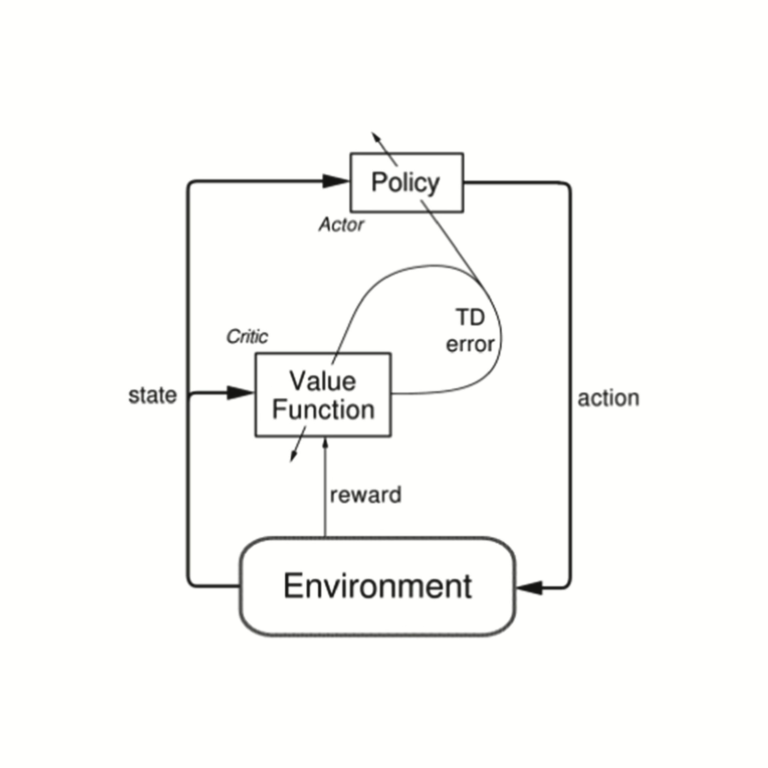

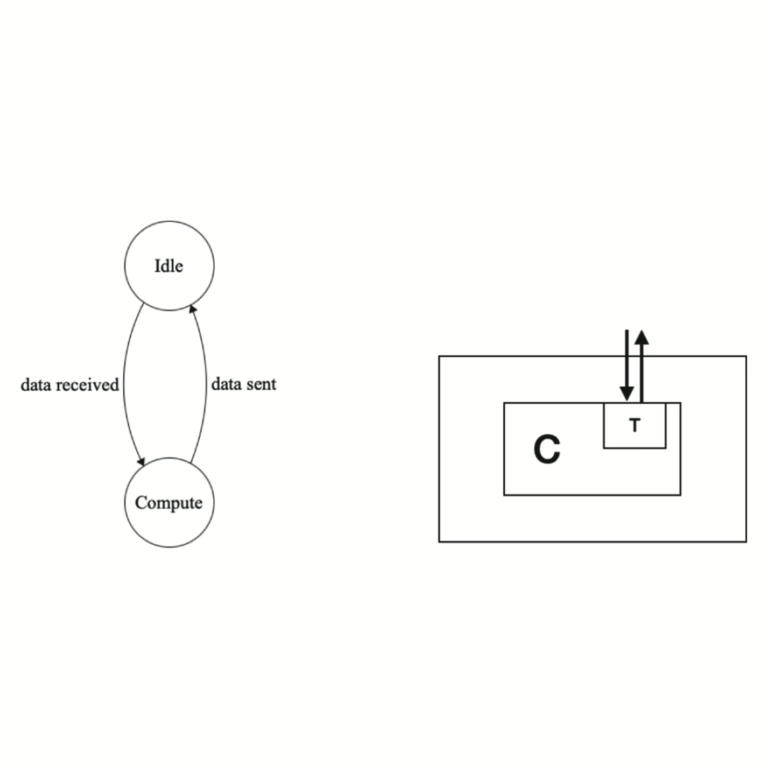

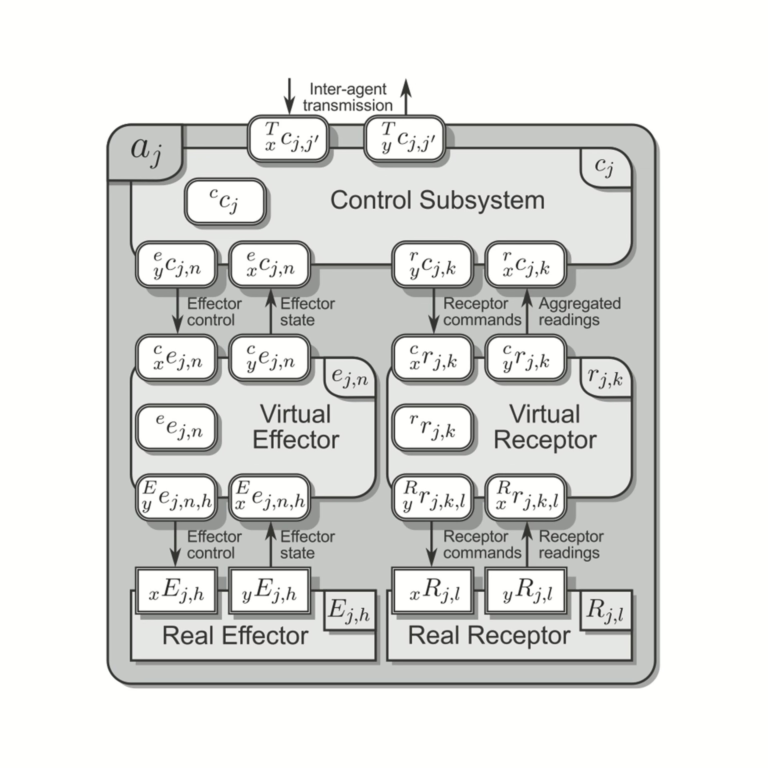

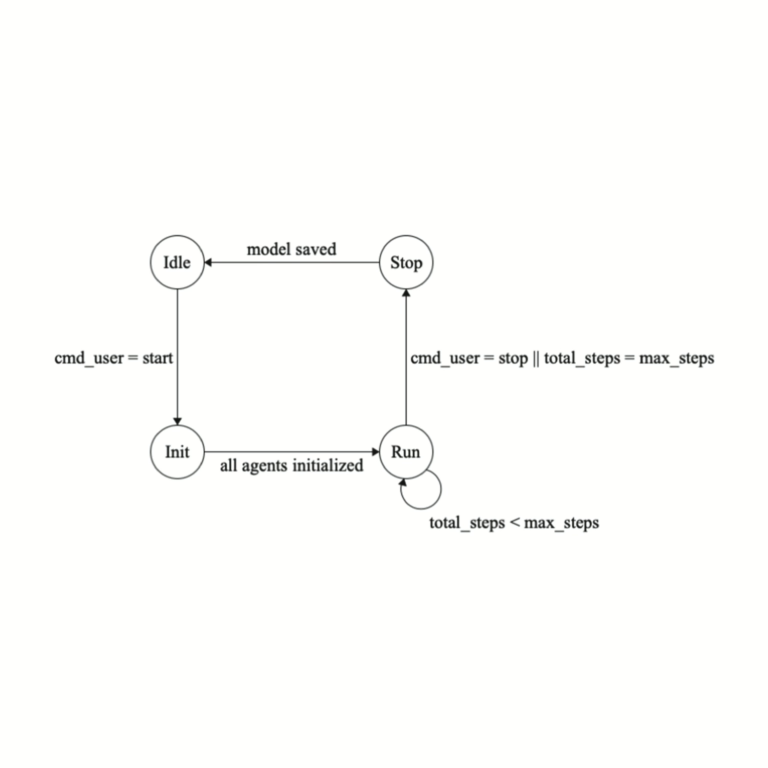

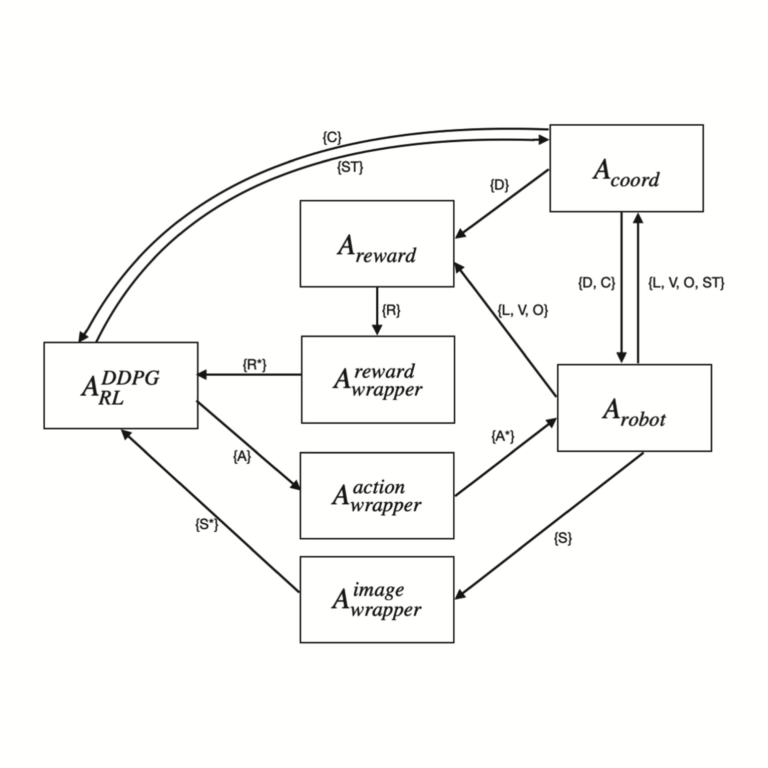

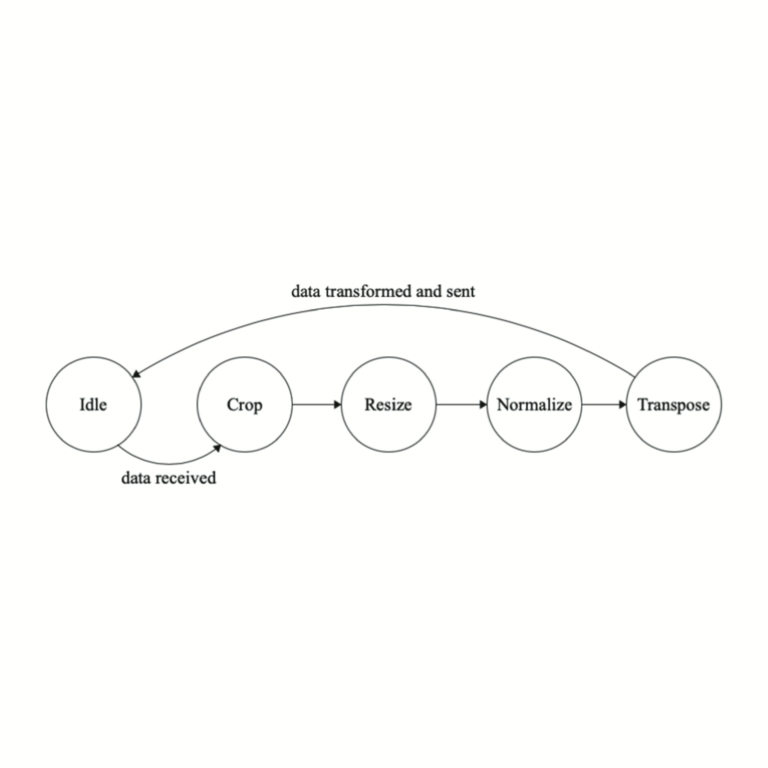

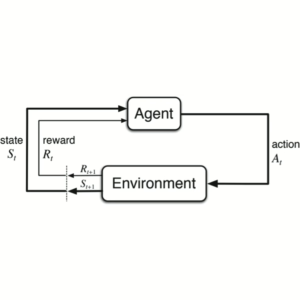

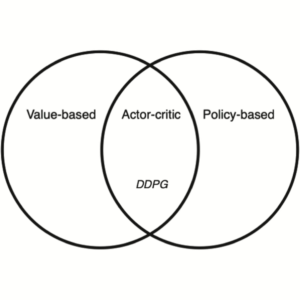

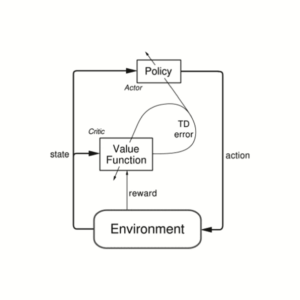

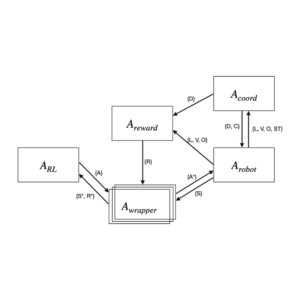

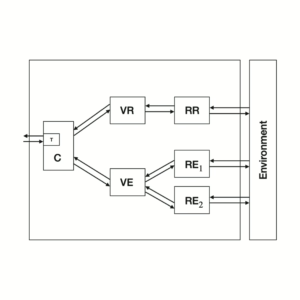

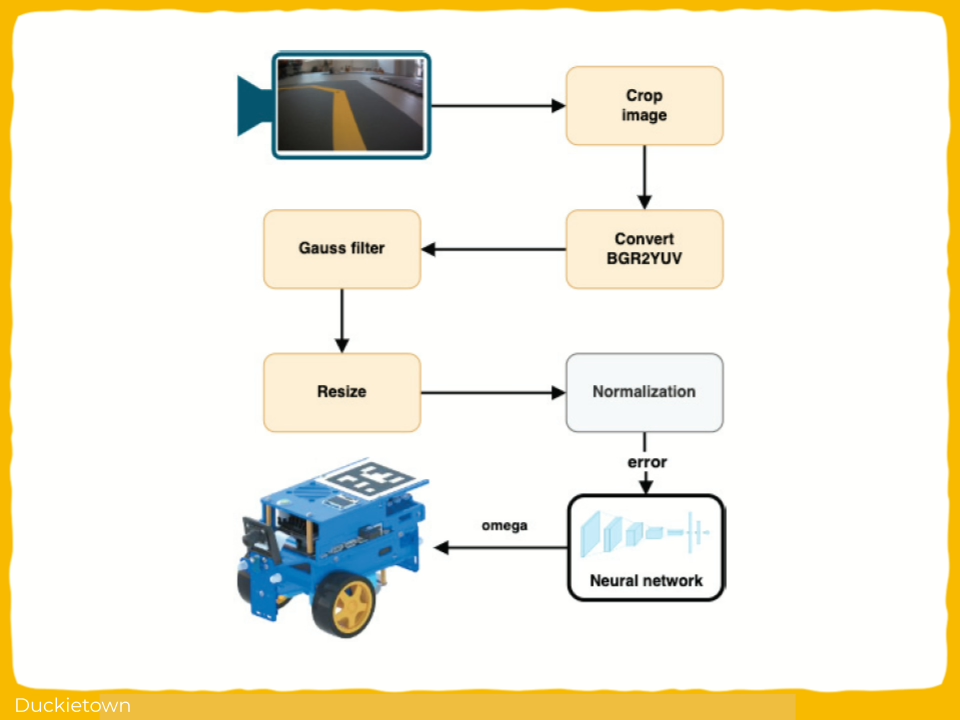

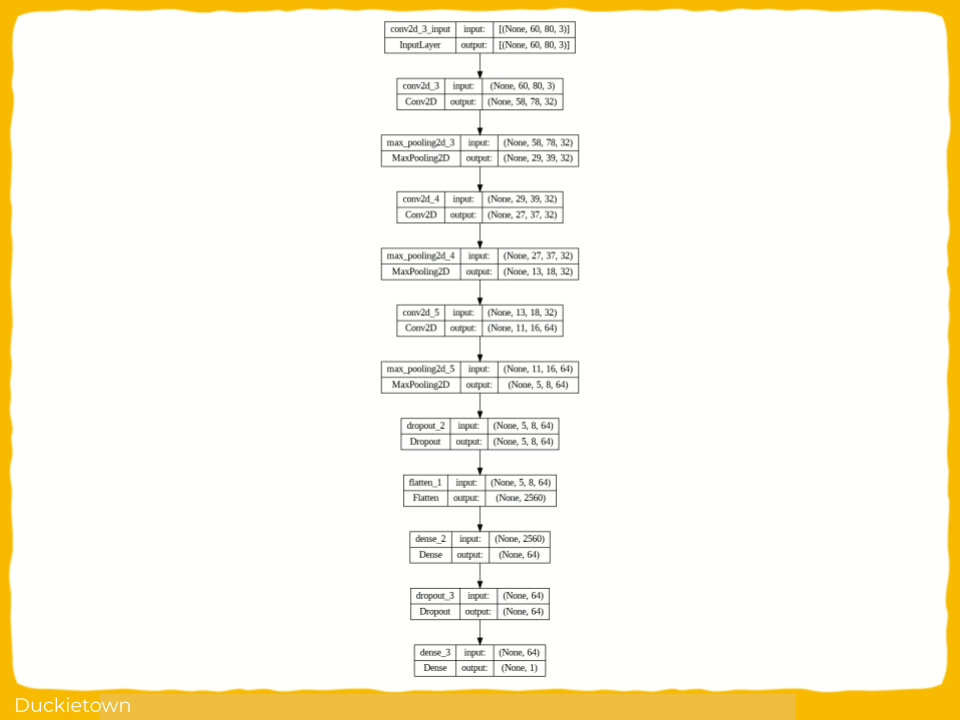

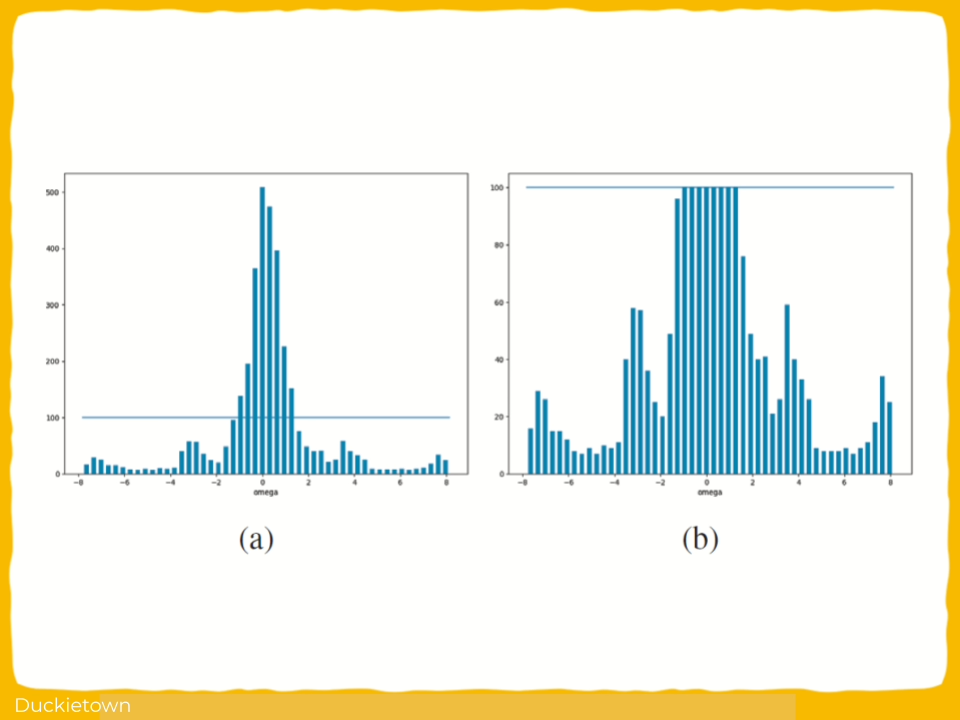

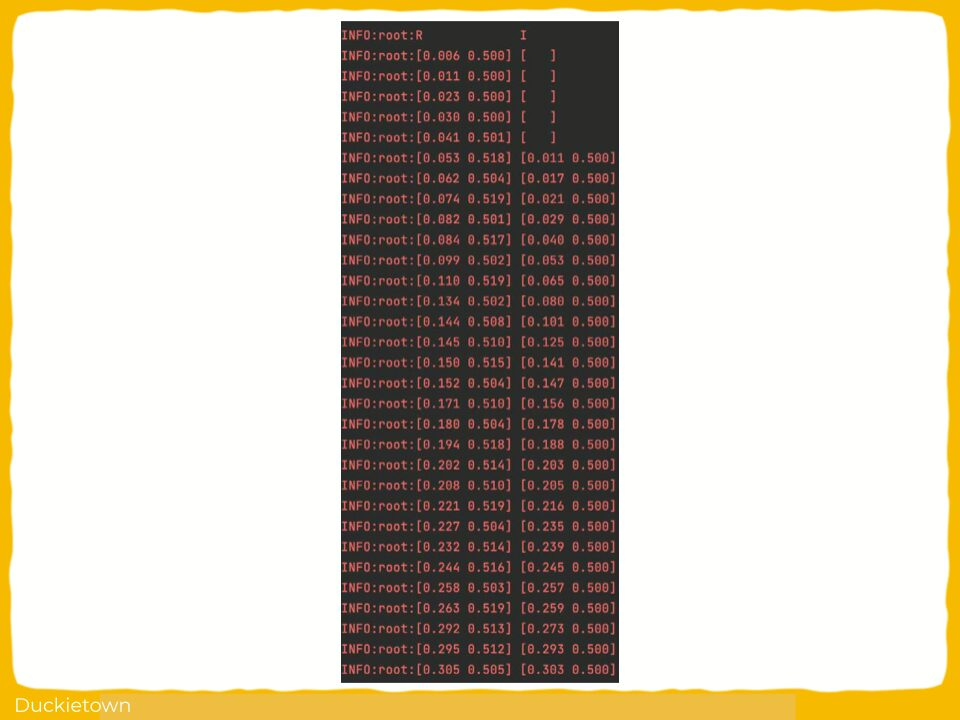

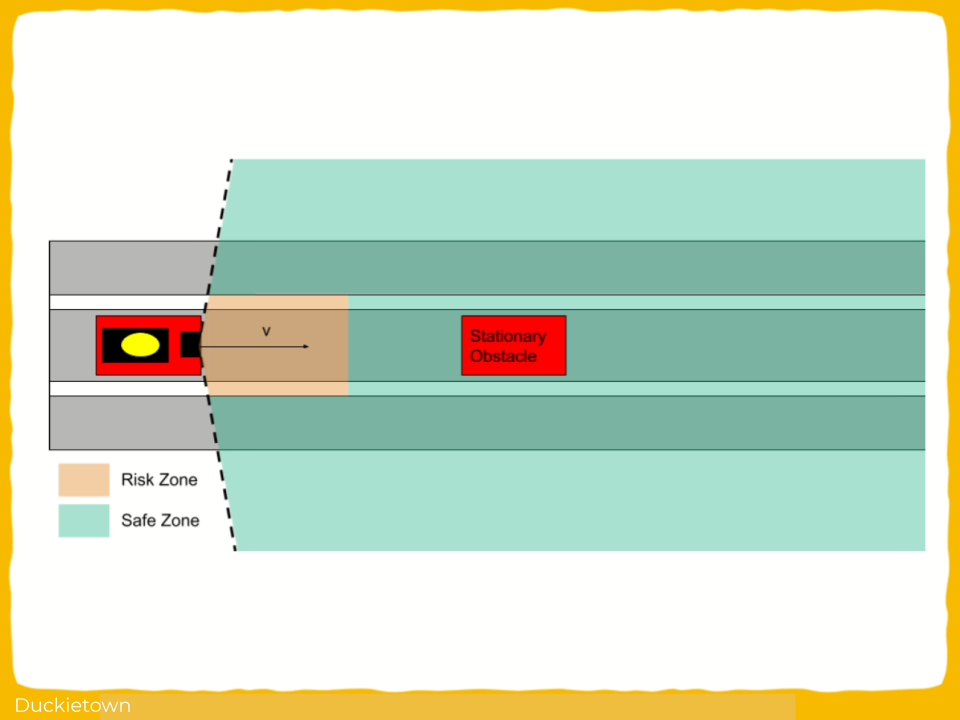

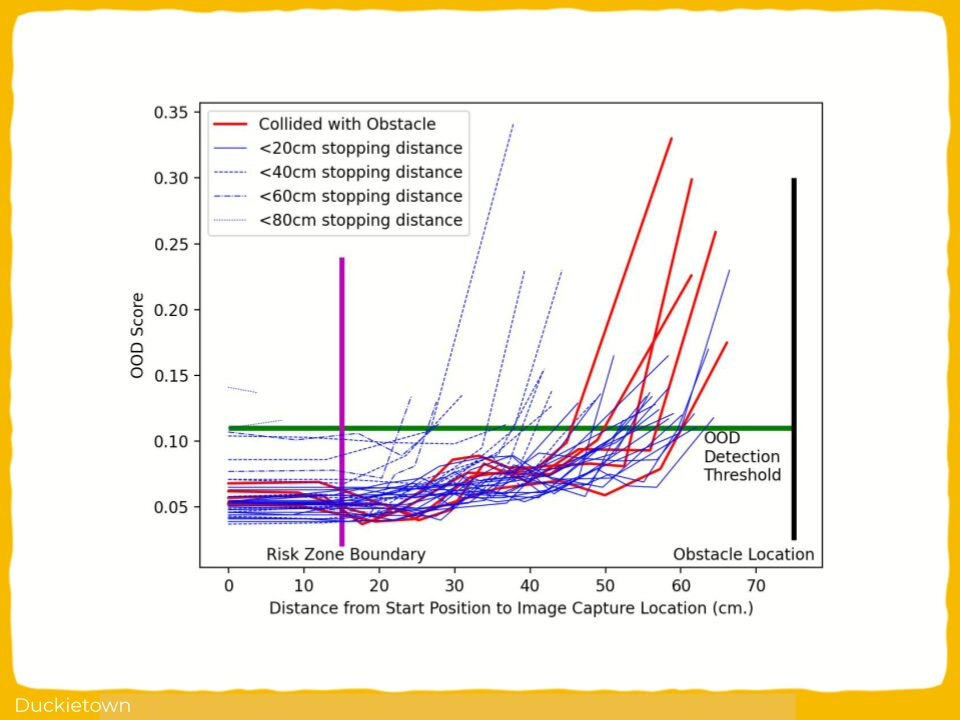

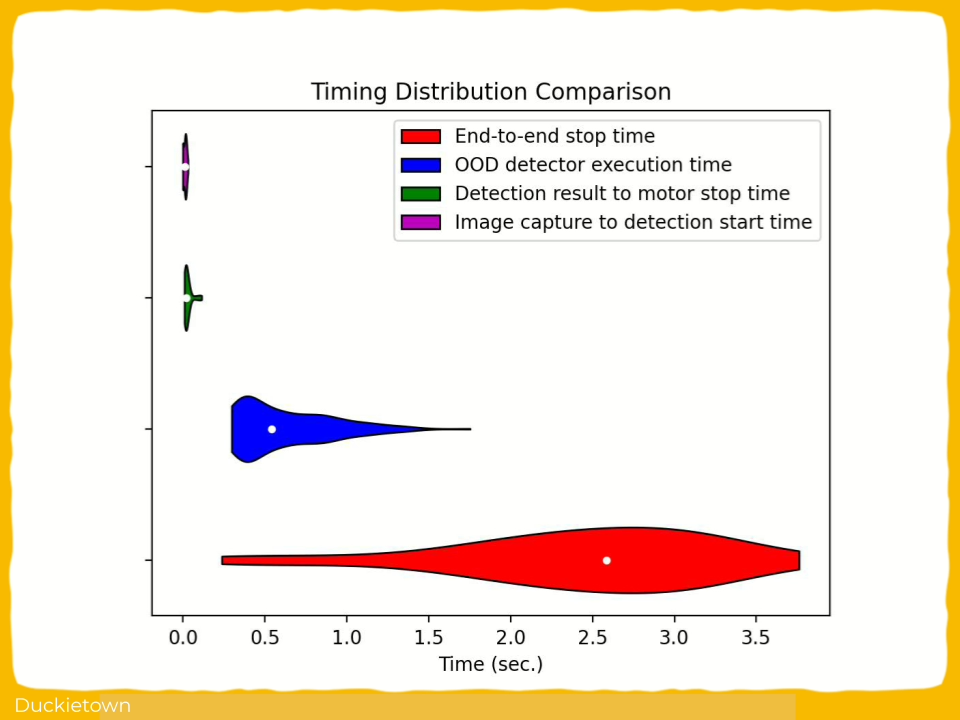

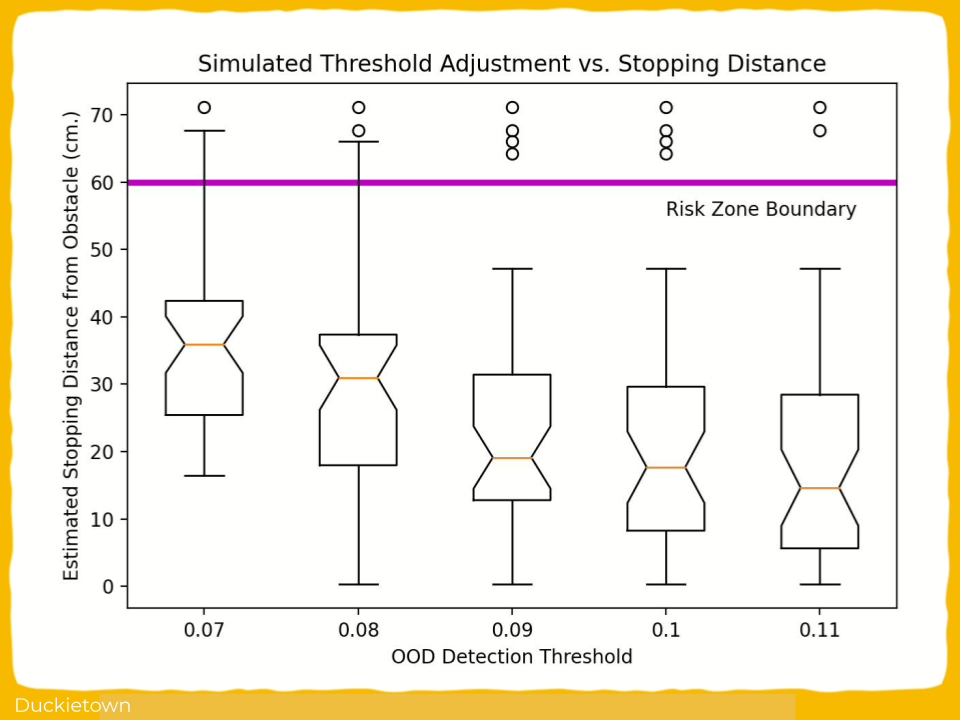

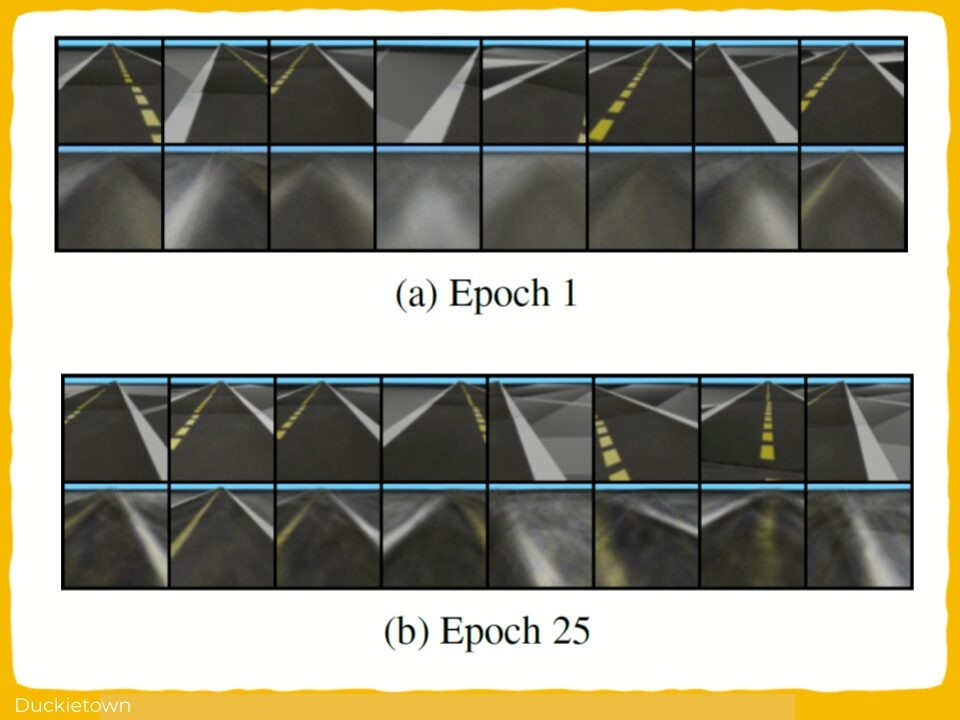

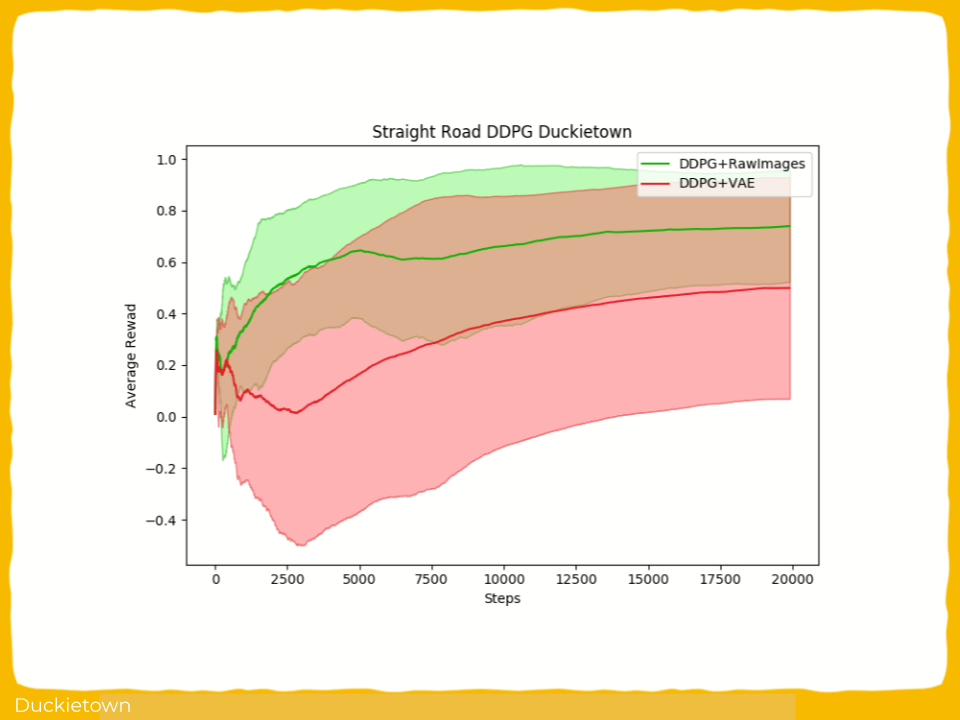

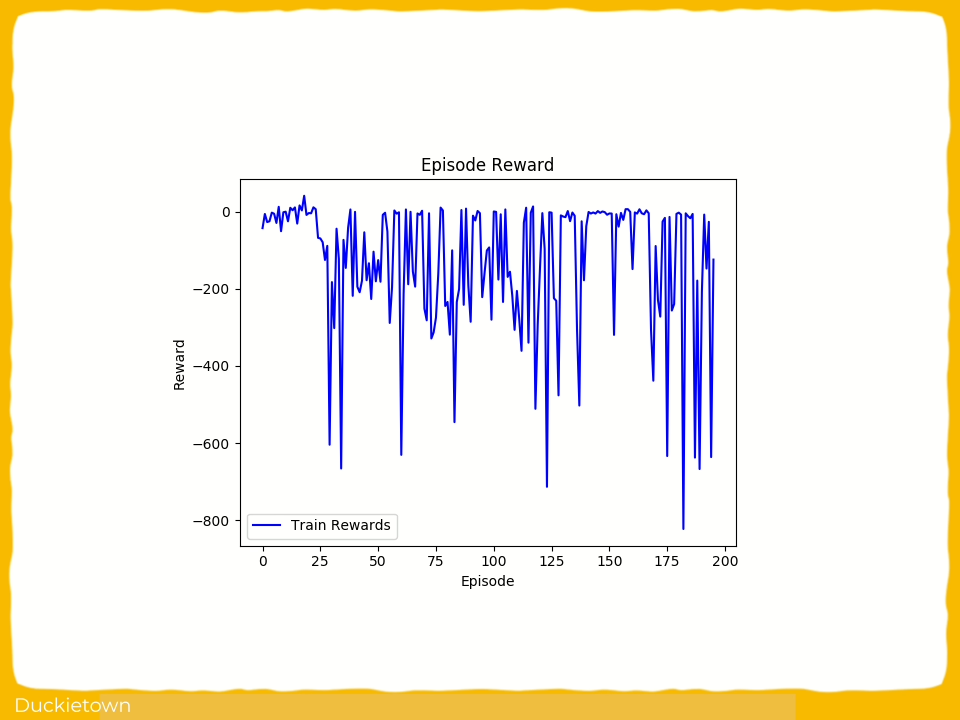

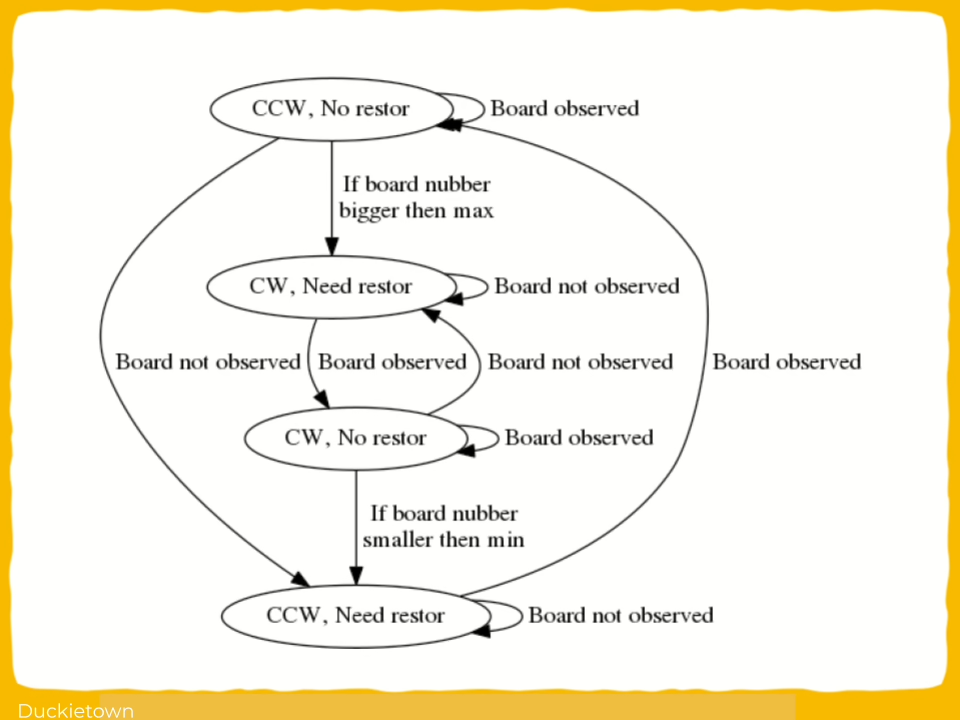

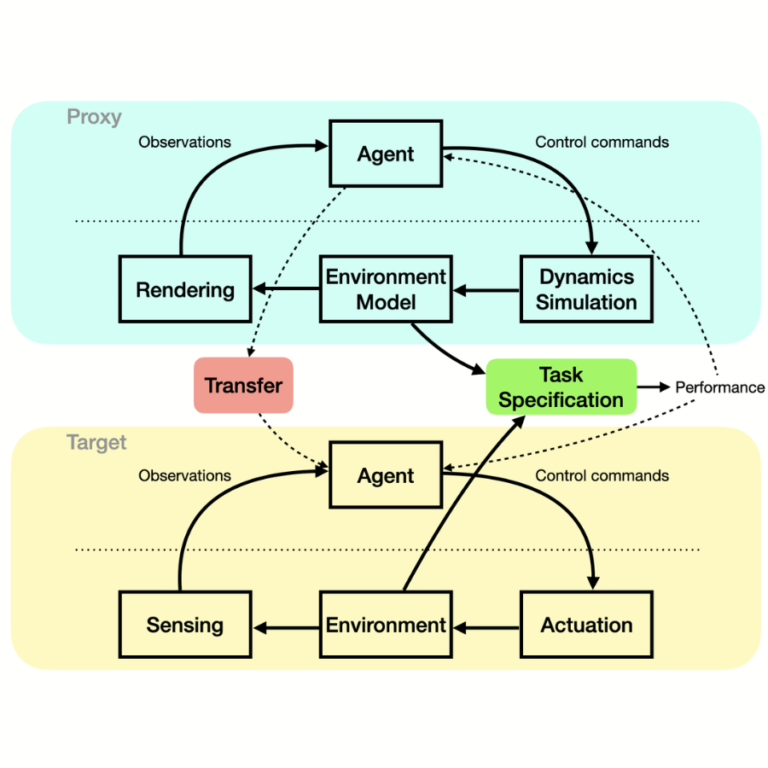

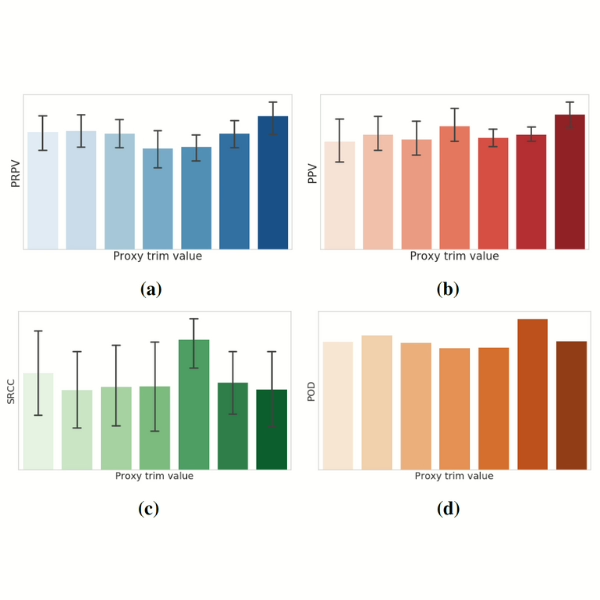

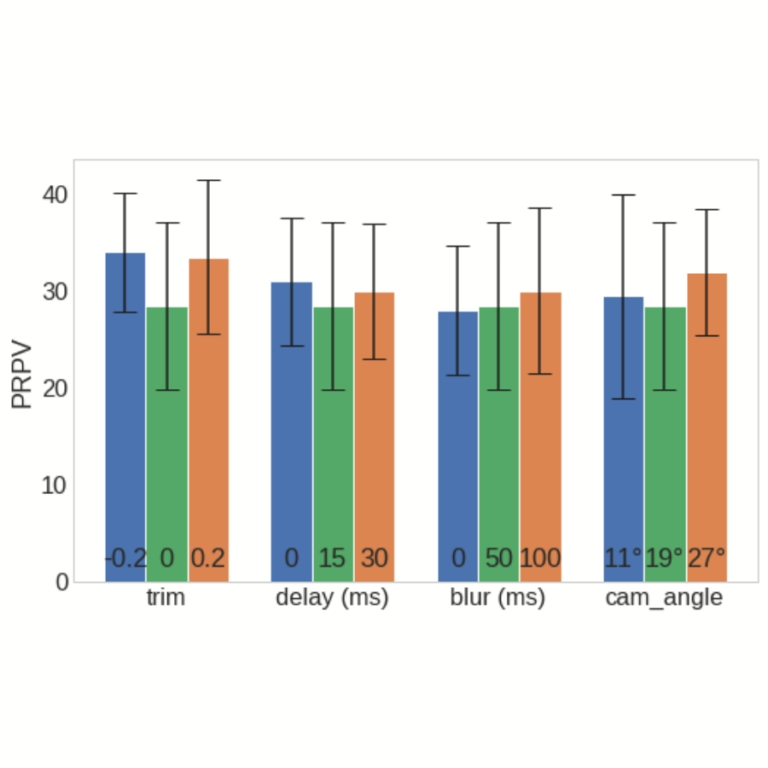

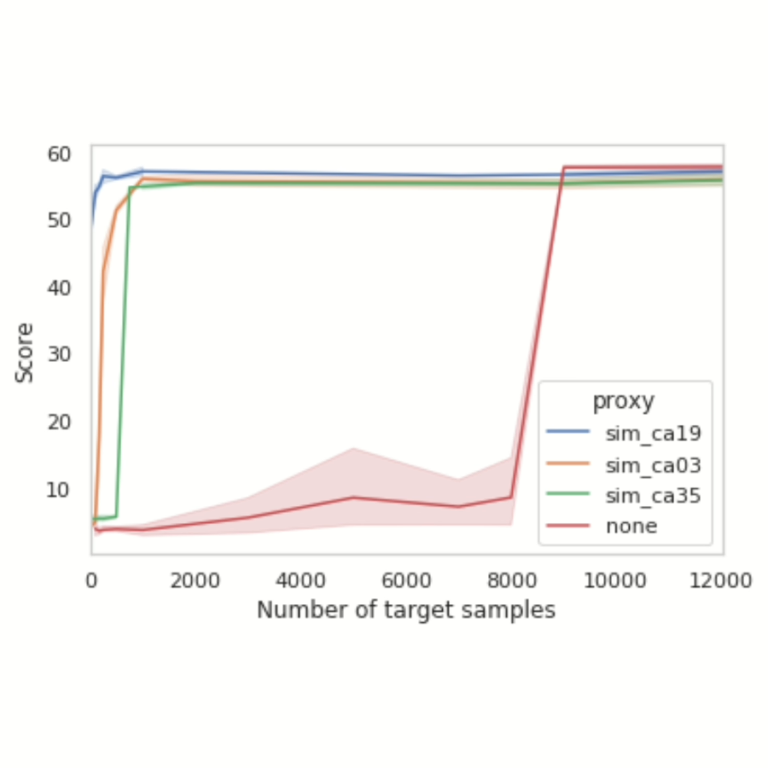

- Proxy Usefulness Metrics: introduction of Proxy Relative Predictivity Value (PRPV) and Proxy Learning Value (PLV) to measure a proxy’s ability to predict real-world performance and aid agent learning. PRPV helps identify simulations that accurately predict real-world results, while PLV measures their effectiveness in training agents.

- Prediction vs. Learning: differentiation of proxies used for accurate performance prediction from those for data generation in training.

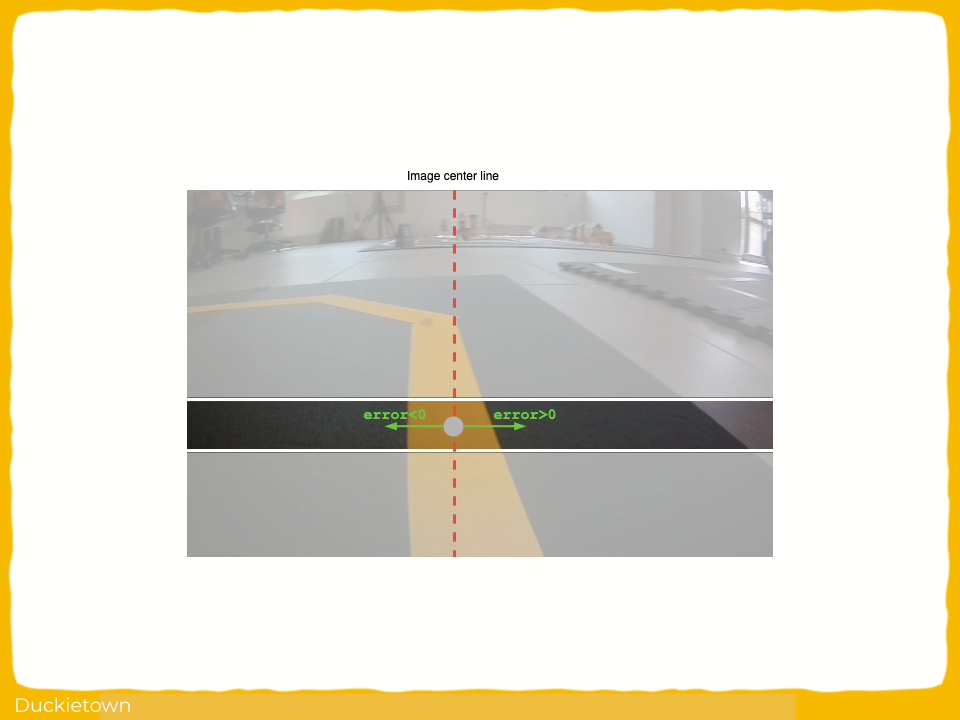

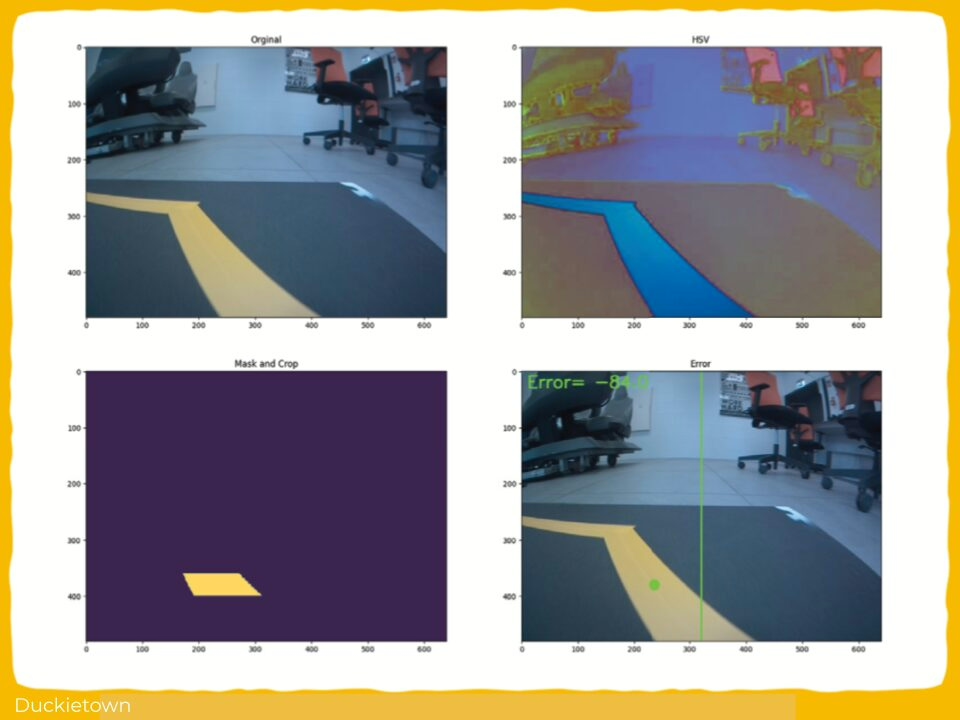

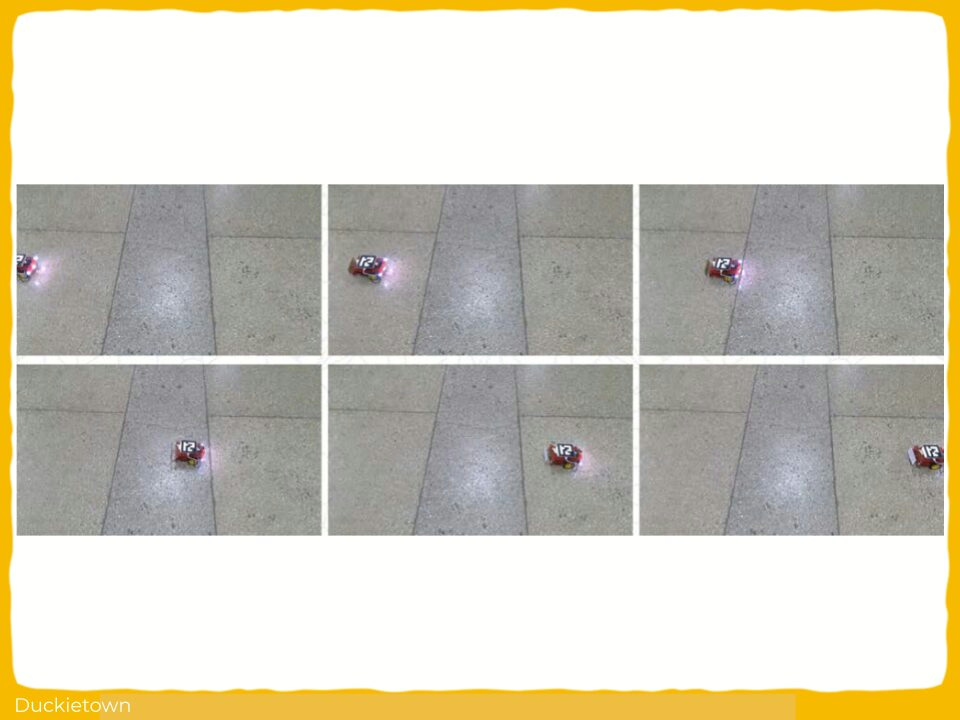

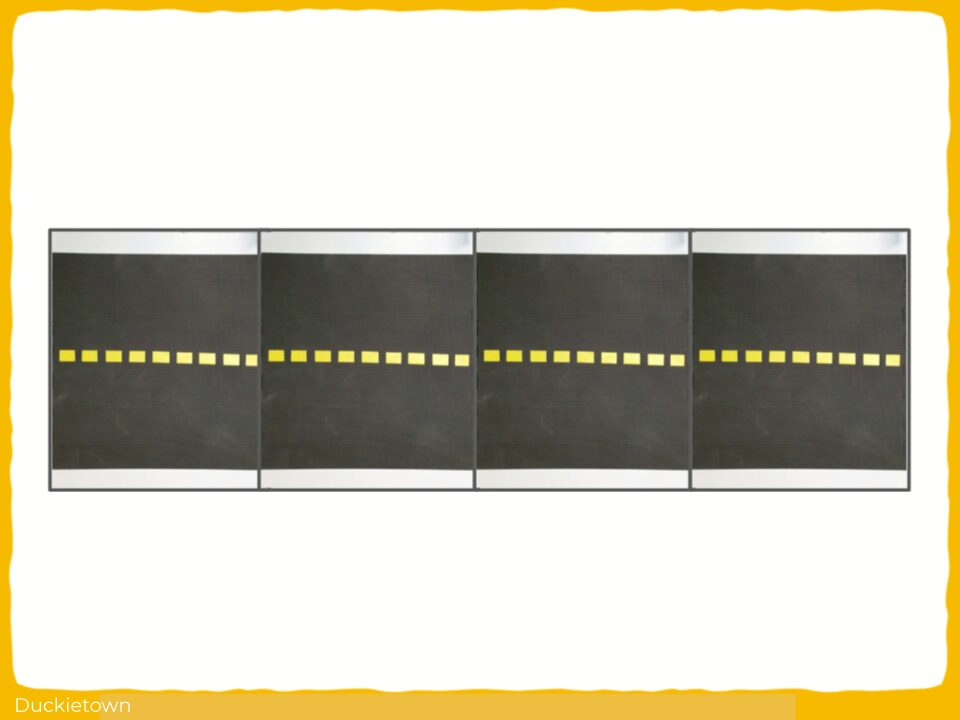

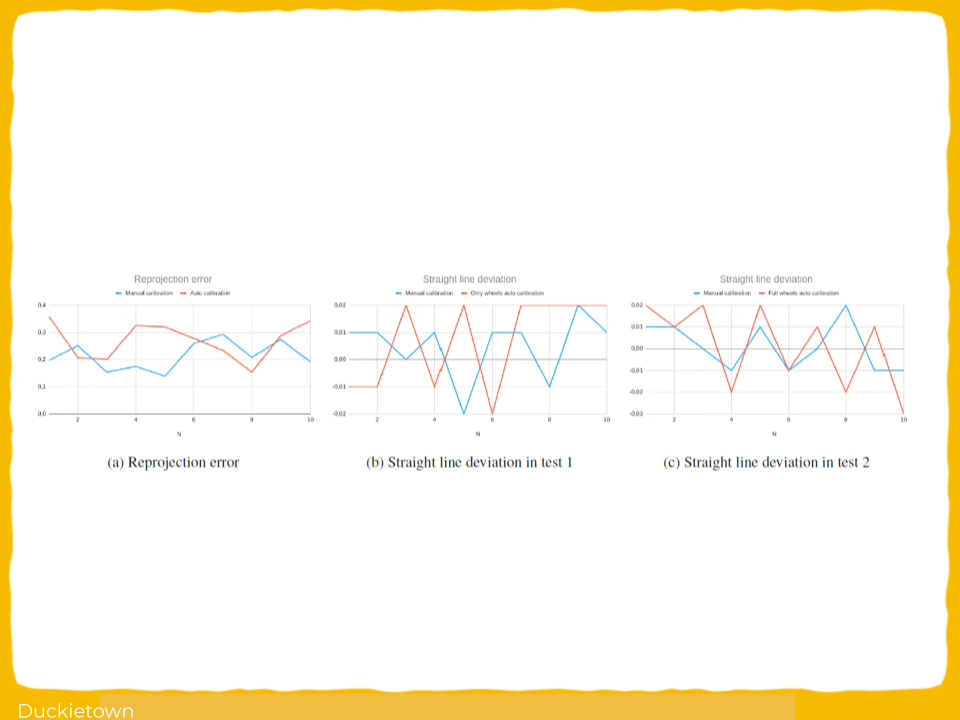

- Experiments: demonstration of how tuning proxy domain parameters (e.g., sensor delays, camera angle) affects predictivity and learning efficiency.

These metrics improve proxy selection and tuning for robotics research and education, and Duckietown enables rapid prototyping of these ideas for mobile autonomous vehicles.

Highlights - Proxy Domains for Evaluation and Learning in Duckietown

Here is a visual tour of the work of the authors. For all the details, check out the full paper.

Abstract

In the author’s words:

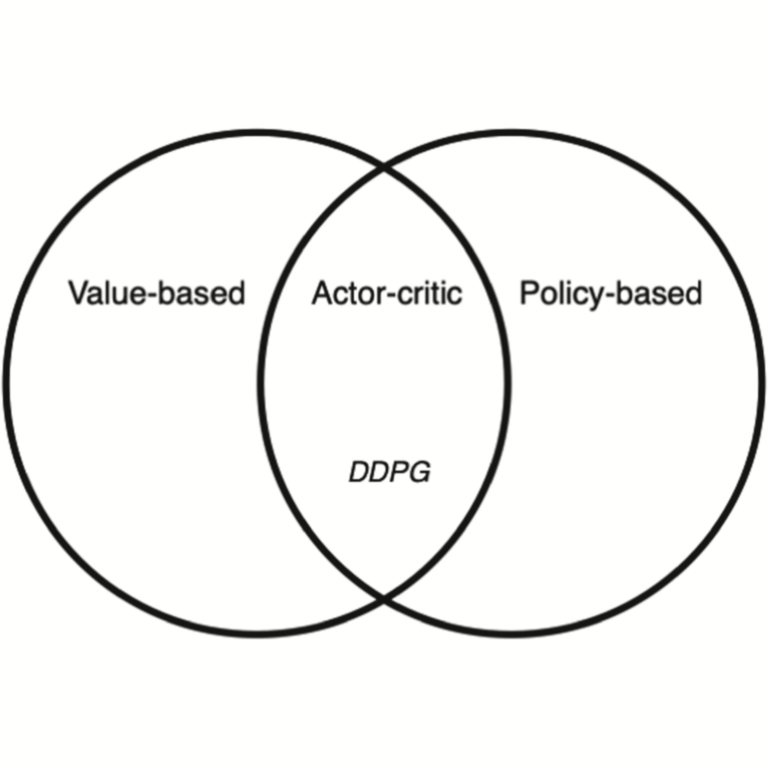

In many situations it is either impossible or impractical to develop and evaluate agents entirely on the target domain on which they will be deployed. This is particularly true in robotics, where doing experiments on hardware is much more arduous than in simulation. This has become arguably more so in the case of learning-based agents. To this end, considerable recent effort has been devoted to developing increasingly realistic and higher fidelity simulators. However, we lack any principled way to evaluate how good a “proxy domain” is, specifically in terms of how useful it is in helping us achieve our end objective of building an agent that performs well in the target domain. In this work, we investigate methods to address this need. We begin by clearly separating two uses of proxy domains that are often conflated: 1) their ability to be a faithful predictor of agent performance and 2) their ability to be a useful tool for learning. In this paper, we attempt to clarify the role of proxy domains and establish new proxy usefulness (PU) metrics to compare the usefulness of different proxy domains. We propose the relative predictive PU to assess the predictive ability of a proxy domain and the learning PU to quantify the usefulness of a proxy as a tool to generate learning data. Furthermore, we argue that the value of a proxy is conditioned on the task that it is being used to help solve. We demonstrate how these new metrics can be used to optimize parameters of the proxy domain for which obtaining ground truth via system identification is not trivial.

Conclusion - Proxy Domains for Evaluation and Learning in Duckietown

Here are the conclusions from the author of this paper:

“We introduce new metrics to assess the usefulness of proxy domains for agent learning. In a robotics setting it is common to use simulators for development and evaluation to reduce the need to deploy on real hardware. We argue that it is necessary to to take into account the specific task when evaluating the usefulness of the the proxy. We establish novel metrics for two specific uses of a proxy. When the proxy domain is used to predict performance in the target domain, we offer the PRPV to assess the usefulness of the proxy as a predictor, and we argue that the task needs to be imposed but not the agent. When a proxy is used to generate training data for a learning algorithm, we propose the PLV as a metric to assess usefulness of the source domain, which is dependent on a specific task and a learning algorithm. We demonstrated the use of these measures for predicting parameters in the Duckietown environment. Future work will involve more rigorous treatment of the optimization problems posed to find optimal parameters, possibly in connection with differentiable simulation environments.”

Project Authors

Anthony Courchesne is currently working as an MLOps Engineer ar Maneva, Canada.

Andrea Censi is currently working as the Deputy Director, Chair of Dynamic Systems and Control at ETH Zurich, Switzerland.

Liam Paull is an Associate Professor at the Universite de Montreal, Canada and also serves as the Chief Education Officer at Duckietown.

Learn more

Duckietown is a platform for creating and disseminating robotics and AI learning experiences.

It is modular, customizable and state-of-the-art, and designed to teach, learn, and do research. From exploring the fundamentals of computer science and automation to pushing the boundaries of knowledge, Duckietown evolves with the skills of the user.